When we talk about saving the bees, we often think of honeybees, hives, and how we can attract these pollinators to our gardens.

We read about neonicotinoids and their devastating effects on honeybees, we petition garden centers to stop selling insecticide-laced “bee-friendly” plants, we see Facebook memes with pictures of half-empty store shelves and captions that warn, “This is what your supermarket will look like in a world without bees.”

And while all of that should definitely influence our landscaping and gardening decisions, we sometimes forget the other bees out there that fly solo and produce no honey, yet are just as important to our food system.

There are over 4,000 species of bees in North America (of which honeybees are a tiny fraction) and they pollinate one-third of our food supply, as well as one-third of the feed for our meat supply (such as cattle).

Read more: Easy Bee Identification: A Visual Guide to 16 Types of Bees In Your Backyard

The troubled honeybee is actually European in origin and was brought here by early settlers. Agriculture in America relies heavily on European honeybees to pollinate important crops like almonds. In fact, millions of hives are shipped hundreds or thousands of miles to the Central Valley in California every year during almond pollination season. With this crucial resource endangered, we need to diversify the bees we depend on because there are many other bees capable of pollinating our crops.

That’s where native bees come in. Unlike honeybees, native bees are gentle, solitary in nature, and require no hive. They include mason bees, leafcutter bees, and bumblebees, and while most of us are familiar with the mild-mannered bumble, many have never heard of masons or leafcutters and their amazing ability to pollinate.

How amazing? It takes only 1 native bee to pollinate 12 pounds of cherries versus 60 honeybees to do the same job!

The reason lies in each bee’s effectiveness in spreading pollen. Whereas honeybees are great pollen gatherers (the pollen is sticky and carried on their back legs, with little pollen falling off as they return to their hive), native bees carry dry pollen all over their bodies that fall off as they buzz from flower to flower. This inefficiency at gathering pollen is the key to the native bee’s success in pollinating a remarkable number of plants in a short amount of time.

Native bees are also less sensitive to weather and start pollinating earlier in the morning and later into the evening than their honeybee cousins. Knowing all this, it only makes sense that we welcome native bees into our gardens (and help increase their populations) by giving them a variety of nectar sources to feed on.

Read next: Foolproof Five: The Best Plants to Grow for Bees

We can take it one step further and provide a safe habitat for these hardworking bees as well. While natives don’t need a hive, they do nest in small, protected cavities where they end up laying their eggs.

Native bee houses are simple structures; essentially they’re a group of hollow tubes placed under the cover of an eave or awning.

You may have even seen DIY native bee houses that consist of nothing more than blocks of wood with holes drilled into them. And while some shelter is better than none at all, these DIY structures eventually become native bee cemeteries as pests take over the holes and there’s no way to clean or inspect them.

I was recently introduced to Crown Bees at the Northwest Flower & Garden Show. Not only was I immediately drawn to their line of native bee houses and accessories, but founder Dave Hunter’s passion for native bees is palpable and he offered to send me their kits to try out. I was intrigued!

A quick browse on the Crown Bees site turns up extensive tutorials and documentation on native bees, how to care for them, how to create a habitat for them, and answers to every question you could possibly come up with. I was excited to start before my native bee kit ever arrived in the mail!

If you’ve never kept native bees before, the kits are the way to go. They include everything you need to set up a safe and attractive native bee house, including the bees.

Yes, they ship bees in the mail — and while I was surprised to hear the little guys buzzing around before I opened my box, I learned that it can happen if the temperatures are just right for them to wake up while still en route.

Native bees from Crown Bees are shipped in their cocoon stage. Depending on the time of year and your particular climate, you’ll receive either spring mason bees or summer leafcutter bees. (These particular ones are mason bees.)

The mason bees come in a little cardboard box with a cold pack, and by the time they arrive at your door, some may have started to crawl out of their cocoons already. Females are larger than males and you can see the difference here in their cocoons.

The males emerge first and if you didn’t know any better, you’d think they were house flies. Native bees are small with hairy black bodies. They’re so gentle that they’ll walk on you without so much as a buzz. You can be close to them without worry of being stung, and in the rare case that you do get stung (usually by accident), it’s fairly innocuous — more like a mosquito bite than a honeybee sting.

I received the Complete Raindrop Kit which included a beautiful wooden teardrop-shaped house, natural lake bed reeds, bee cocoons, and some accessories.

Lake bed reeds are ideal nesting tubes for native bees. They’re preferred over tearable paper tubes, and they’re much easier to maintain than rigid bamboo reeds. They come in an assortment of hole diameters for all the different bees that might visit your garden. Think of them as hotel rooms in your bee hotel.

To create the uneven, irregular environment that native bees prefer, I added a few sticks of varying lengths and widths. The sticks are placed with the reeds to help the female bees locate their nesting holes.

When arranging the reeds inside the bee house, I pulled a few of them out at random, just slightly, so they aren’t fully flush. They act as a marker so that the bee will come along and think, Oh, there’s my room next to the large overhung twig.

Hanging the bee house takes some consideration. It should be under an eave, protected from rain and wind, and positioned in a spot that soaks up the warmth of the morning sun (but stays sheltered from harsh afternoon sun in hotter climates). Ideally it should also be at eye level so you can keep tabs on the bee activity.

Native bees don’t like to be disturbed so once their bee house is mounted, it should not be moved until the end of the native bee season in autumn.

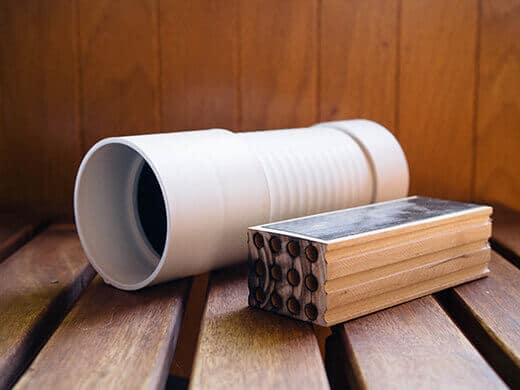

To compare the different types of native bee houses, I also hung a BeeHut in another part of the yard. This simple plastic bee house (which looks like PVC pipe) comes with a reusable wood tray. The tray is actually five slim trays stacked on top of each other, creating nesting holes for mason bees.

In the fall, you can remove the black adhesive tape and disassemble the trays to harvest the cocoons and clean the cavities as needed. (Harvesting just means you bring the cocoons inside for winter and store them in the fridge to protect them from parasites; the same goes for cocoons you eventually harvest from reeds.)

We painted the BeeHut (with water-based non-toxic paint) so it would blend in better with our house.

Once the bee houses are hung, there’s not much left to do. It’s like hanging a bird feeder — only occasional maintenance is needed. Just keep an eye on the nests to ensure birds, squirrels, and other critters aren’t making a meal out of your native bees (a screen placed over the holes should help with that problem). Enjoy watching the bees move in and out of their bee house all season long and seeing your melon crop flourish!

Crown Bees has a number of bee houses and accessories to get you started on “keeping” these gentle solitary bees. I’m partial to the Raindrop house as I think it’s a beautiful addition to the garden, but they carry a variety of structures to suit every style.

(As an aside, please avoid the $20 made-in-China knockoff with woven bamboo sides. Yes, it looks cute, but it will last as long as $20 lasts you and does not come from a company that actually cares about native bees and your success with them. Ethically, I feel better supporting a company like Crown Bees in this regard.)

I also recommend signing up for their Bee-Mail, which sends you email reminders on what to do and when to do it throughout the year. Very helpful as I venture into this new territory of native bees!

More beneficial insects to make friends with:

- Easy Bee Identification: A Visual Guide to 16 Types of Bees In Your Backyard

- Yikes—Do Potato Bugs Bite? Here’s the Lowdown on Jerusalem Crickets

- How to Attract Ladybugs to Your Garden (and Why You Want To)

This post is brought to you by Crown Bees. Thank you for supporting the sponsors that support Garden Betty.

Alma Rios Barraza liked this on Facebook.

Kim Griffin liked this on Facebook.

Monica Koler liked this on Facebook.

Angie The Freckled Rose liked this on Facebook.

Holly Curl German liked this on Facebook.

Azita Toucourt liked this on Facebook.

Greg Hadel liked this on Facebook.

Cindy Deraiche liked this on Facebook.

Greg Towne liked this on Facebook.

Bill Will liked this on Facebook.

Scott C. Poole liked this on Facebook.

Emily Trudeau liked this on Facebook.

Annette Garvey liked this on Facebook.

Sara Bendrick liked this on Facebook.

Kandy Leggett liked this on Facebook.

Taylor Lauryn Ray liked this on Facebook.

Angie Smith liked this on Facebook.

Marie Tom liked this on Facebook.

Jamie Huff Smith liked this on Facebook.

Amy Kaiserski liked this on Facebook.

Zelma McTurnan liked this on Facebook.

Laurin Lindsey liked this on Facebook.

Tiana D Preston liked this on Facebook.

Desleigh Whatmough liked this on Facebook.

Denise Petro Lewellyn liked this on Facebook.

Gogo Perkins liked this on Facebook.

Theresa Young liked this on Facebook.

Clayworks Farm liked this on Facebook.

Linda Enteles liked this on Facebook.

Jim Lynn liked this on Facebook.

Patricia Tippens Armour liked this on Facebook.

Linda A Conner liked this on Facebook.

RT @theGardenBetty: RT @WendyGMG: Great how-to post on raising native #bees + fun photos! http://t.co/CxSTnjxV13 @theGardenBetty http://t.c…

RT @WendyGMG: Great how-to post on raising native #bees + fun photos! http://t.co/CxSTnjxV13 @theGardenBetty http://t.co/jljoAA3Lz6

Let’s Talk About Native Bees and Why We Need Them http://t.co/4RD0RwkApL #gardenchat < TY for RT! @jennyMsauer @sctrailfriends @StoneWerks

RT @theGardenBetty: To #savethebees, we should diversify. Let’s Talk About Native Bees and Why We Need Them http://t.co/qeqRB6xh97 < TY for…

To #savethebees, we should diversify. Let’s Talk About Native Bees and Why We Need Them http://t.co/qeqRB6xh97 < TY for RT! @TheDivineNomad

Let’s Talk About Native Bees and Why We Need Them http://t.co/4RD0RwkApL #gardenchat < TY for RT! @jonbkoch @A_Bloke_Cooking @iamgreenbean

RT @theGardenBetty: To #savethebees, we should diversify the bees we depend on. Let’s Talk About Native Bees and Why We Need Them http://t.…

To #savethebees, we should diversify the bees we depend on. Let’s Talk About Native Bees and Why We Need Them http://t.co/qeqRB6xh97