I had always heard about a certain part of New Mexico called “Georgia O’Keeffe country,” but I never really knew what it meant or how the American modernist painter came to own the landscape.

In the 1930s, Georgia O’Keeffe moved from New York City to Abiquiu, New Mexico, a Spanish Colonial-era village that at one time was the third largest settlement in the New Mexico Territory. O’Keeffe restored an old adobe compound in Abiquiu where she lived until 1984, two years before her death. Just outside her window were the stunning landscapes of Northern New Mexico from which she drew boundless inspiration for her famous paintings.

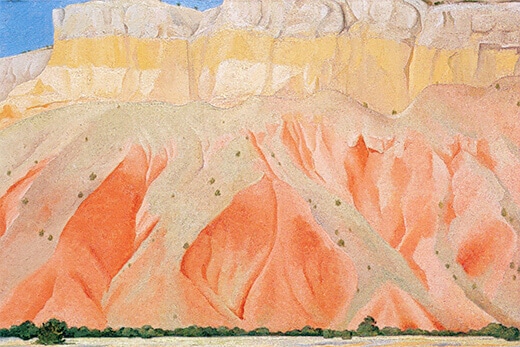

Image by Georgia O’Keeffe Museum.

According to O’Keeffe, “When I got to New Mexico that was mine. As soon as I saw it that was my country. I’d never seen anything like it before, but it fitted to me exactly. It’s something that’s in the air, it’s different. The sky is different, the wind is different. I shouldn’t say too much about it because other people may be interested and I don’t want them interested.” (From Perry Miller Adato’s documentary film, Georgia O’Keeffe.)

Her words couldn’t ring truer, because as we passed through the less-tracked wilderness of Chama Canyon in Santa Fe National Forest, we too felt an innate connection with the land that we wanted to keep to ourselves.

In the middle of our Southern Colorado road trip, Will and I took a detour to New Mexico to embark on a 31-mile, 3-day, self-guided kayak camping tour down the Rio Chama.

A designated Wild and Scenic River and major tributary of the Rio Grande, the Rio Chama cuts through the Rio Chama Wilderness, a primitive area encompassing 50,300 acres in Northwestern New Mexico. Wild and Scenic Rivers represent the wild and untouched landscape of America accessible only by trail. Paddling down this beautiful ribbon of water meant we would get to see the rare forms of nature that few people ever see in their lifetimes.

The Bureau of Land Management limits access to the Rio Chama as a conservation effort, and “private party” permits are needed to run the river in the summer. We lucked out as we were able to score a permit less than a week before our trip, and the river was scheduled to be dammed the following week. There was still enough water flow in the canyon to make kayaking possible, and with it being so late in the season, we would nearly get the whole river to ourselves.

After crossing the border from Southern Colorado to Northern New Mexico, we reached the rustic fishing resort of El Vado Ranch in Tierra Amarilla, the put-in for our kayak adventure.

We packed three days’ worth of food and camping gear into our kayaks, along with extra supplies to comply with the river’s “Leave No Trace” policy. Packing for kayak camping always involves a “duffel shuffle” as we decide what to load into Will’s hard shell and my inflatable. On this trip, he carried our tent and sleeping bags, while I carried our food and clothes.

We love kayak camping — it’s like the lazy man’s backpacking. You can bring all your gear with you into the wilderness, but don’t need to hoof it with 50 pounds on your back. Sometimes you don’t even need to paddle. The serenity of floating along the water brings you that much closer to the earth, and you tend to notice the little details that often get lost when you’re scrambling up a trail…

Shadows cast by ponderosa pines. Natural mulch on the forest floor from years of peeling bark. Colonies of swallows’ nests clinging to the undersides of cliffs.

The first day on the river offered gentle Class I and II rapids flanked by desert brush and rocky slopes.

We passed an old 1800s homestead and a small guided group of rafters, but beyond that was pure isolation.

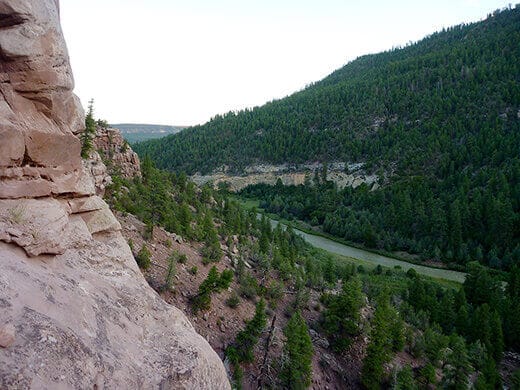

As we paddled deeper down the river, the landscape gave way to an evergreen-filled canyon and steeper, more dramatic walls.

We pulled off onto a riverbank for lunch, which consisted of our backpacking staples of tortillas, turkey, cheese, hummus, and garden-grown veggies brought from home.

This turned out to be one of the most beautiful tomatoes I’ve ever grown — just look at that color! And the flesh was so dense and juicy, I could’ve eaten the whole thing like a peach. A sweet, smoky peach. (In case you’re wondering, this was a Cherokee Purple tomato, an heirloom variety that ranges from a deep crimson color to a dark purple when mature.)

After lunch, we settled into camp for the evening. With riverfront accommodations and an open-air lounge, I was seriously loving life.

Sometimes I wonder why I bother bringing all that camping gear with me, because I often feel perfectly content just sleeping on the ground under a canopy of trees.

A short scramble up a cliff for a view and a cuppa vino rewarded us with an overlook of the river.

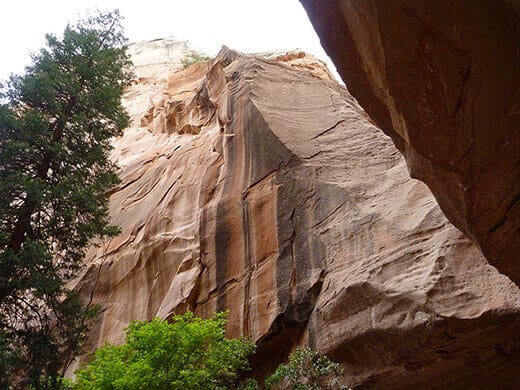

Next to the steep walls of Chama Canyon, which rose 1,500 feet above the river, the Rio Chama was merely a sliver.

The next day we awoke to a nearly cloudless sky and set off on day two of our journey.

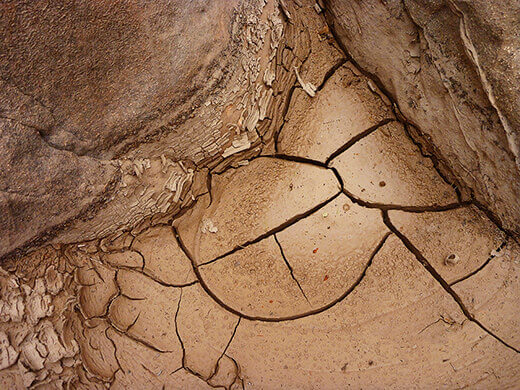

We passed impressive cliff bands of sandstone, shale, granite, and basalt that formed during the Triassic and Jurassic periods. In fact, along the river are fossilized footprints from an Allosaurus (an ancestor of the Tyrannosaurus rex) that used to roam the land 150 million years ago.

For the next 10 miles, the canyon walls towered over us, striped in vivid shades of vermillion, pink, yellow, and white. I think I wore a permanent expression of awe that whole day.

The canyon grew taller and narrower as we neared our second campsite, a tip given to us by a river guide who had told us it was her favorite site on the whole stretch.

Finding this secret spot required a “hot landing,” as it was called, which meant the pull-out was in the middle of a small but swift rapid. A short walk brought us to the campsite, tucked underneath a stand of trees.

A beautifully gnarled old tree was the centerpiece of our site, as well as our clothesline.

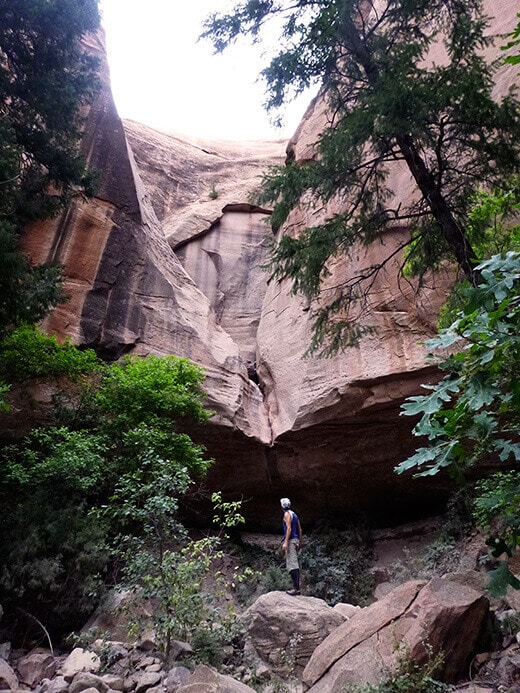

We had heard about a trail that started near our campsite and led into a slot canyon so secluded and spectacular, it was dubbed your “own private Utah” by local guides and rivaled some of that state’s classic sandstone features.

Along the trail, we found skeletal odds and ends from an animal, its bone fragments bleached by the sun.

We kept finding more and more bones…

… Until we hit the jackpot! A vertebrae!

Of course, the zooarchaeologist in me had to dig in a little deeper.

I surmised the remains might have come from a mountain lion. Or something very big, very scary, and not a creature we’d want to run into on our hike. The dead one, or the one that killed it.

It was hard not to feel apprehensive after our little discovery, especially since the sun would be setting in an hour and big, scary creatures likely prey on defenseless kayakers at night. But, we didn’t have to hike much further before coming upon the slot canyon.

The sheer sandstone walls seemed amplified at such close range, and standing next to them reminded us how insignificant we really are in this world. Insignificant, yet we can do so much damage to the places that have been here eons before us.

It truly was our “own private Utah”… but even better, because it was New Mexico and no one knew about it.

And we even made it out of the slot canyon without getting eaten by any creatures of the night.

As for our campsite… we’ll leave it a locals’ secret for now.

Our final day on the river greeted us with more sunny skies. We were exceptionally lucky the last few days, because while summer monsoons were looming over Southern Colorado just a couple hours away, we had nothing but warmth and sunshine on our skin.

We kayaked a few miles of calm, flat water and the only sounds came from the splashing of our paddles.

In this extraordinarily serene stretch of the river, we passed the Monastery of Christ in the Desert, a Roman Catholic Benedictine monastery. Out there in the Rio Chama Wilderness, the monastery maintains one of the largest private solar arrays in the country, which power its electricity and water pumping. I wish we’d had time to visit the monastery after our river journey, because the architecture (by Japanese-American woodworker George Nakashima) and the network of sustainable systems employed at the monastery — not to mention the devout lifestyle of Benedictine monks — are endlessly fascinating.

As I sat in my kayak, enjoying the solitude of the moment in this designated quiet zone, I could not imagine a more perfect place to be cloistered. In a different life, I too might have considered becoming a monk if the Chama were my backyard.

The last several miles of our journey were outside of official “Wild and Scenic” boundaries, and signs of civilization started to appear with small homes, some built in traditional adobe style, flanking the riverbanks. No longer wild, but still very scenic.

We floated lazily on the river past more incredible landscapes. It was not until the last couple miles that the river served us a lively series of Class III rapids to end our trip on an adrenaline-charged note!

After 31 miles, 3 days, and only 1 capsize, we finally reached the take-out at Big Eddy in Abiquiu, New Mexico. In all our kayak camping adventures, the Rio Chama ranks highly as one of our ultimate favorite trips, both on water and on land.

After packing up the car and changing into fresh clothes that didn’t involve a bathing suit, we were off.

As we drove through Georgia O’Keeffe country, admiring the desert landscapes that she made famous, we too felt something different… in the air, the sky, and the wind.

Where there only class I rapids on this stretch? Also, would it be possible to do a longer stretch? I want to do a 4 day 3 night trip next June.

The first 20 miles are Class I and II, and the last 10 miles have some fun Class III wave trains. However, you can avoid the Class III run by taking out at the long flat section near the monastery (some kayakers actually put in here, as they only want to run the Class III).

The full 30-some-mile stretch starts at El Vado and ends at Big Eddy. I’m not aware if you can put in or take out outside of these spots.

Thanks. Y’all did the whole 30 miles in 2 days right? How many hours per day did you paddle. I want to stretch it over 3 days. Also how did y’all get back to your car where you put in at? We will have two cars so is there a place we can park one at the put in and one at the take out?

We paddled the river in 3 days; roughly 10 miles per day. We used a shuttle service, but you can park a car at El Vado Ranch (not sure if there are any fees) and another car in Abiquiu near Big Eddy. Definitely research the parking options in Abiquiu, since you want a spot that will be fairly secure for the 3 days you’re gone.

can you provide details on transportation and rentals to and from Big Eddy

If you need rentals and transport, I suggest you look into a rafting outfitter like Far Flung Adventures in Taos; I met a couple of their guides on the river and they seemed like a great operation.