If you live below USDA hardiness zone 8, you’ve probably written off winter gardening.

And for a while, I thought the same way. I garden in a zone 5 microclimate at 4,000 feet elevation, where our frost-free growing season is (at best) only 50 days out of the year. (Use my interactive tool to find out how many frost-free days you have in your area.)

But through trial and error, I’ve learned that a hard frost does not usher in the end of the season. Even as my fall crops start to fade and the weather turns more wintry, my garden is still—and will be—producing through the holidays and beyond.

I’ve actually been busy sowing seeds and getting transplants in the ground before the soil freezes. In the ground—not in a greenhouse or high tunnel, but right in my backyard in the same raised beds I’ve been using all year.

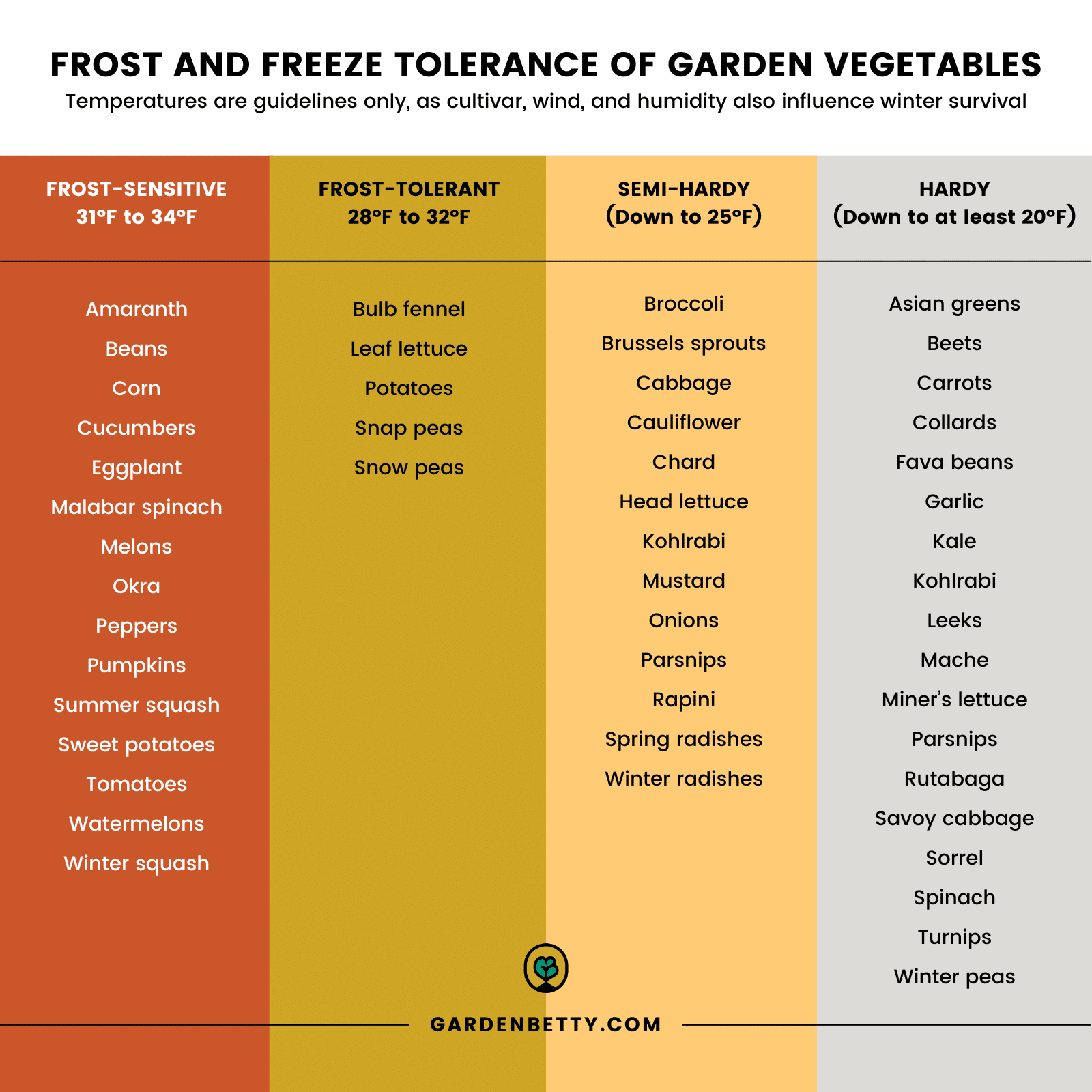

This might raise an eyebrow if you’ve resigned yourself to thinking winter gardening is impossible in your zone. And if you’ve ever seen those tables showing the minimum temperature limits for growing vegetables, you’ve likely assumed that gardening ends when winter temperatures plummet to 20°F or below.

However. I’m here to tell you that there’s no need to throw in the trowel. I’ve grown all of the vegetables listed on the right side of this table through my zone 5 climate (down to single-digit temps in the depth of winter).

Frost-tolerance lists like this one are merely guidelines—you can “cheat” winter just by knowing how plants respond to the cold.

How plants adapt to freezing weather

Cold-tolerant plants have unique adaptation that help their tissues better respond to freezing conditions. They compartmentalize freezing by moving most of the water outside of their plant cells to freeze (which is why frozen plants appear wilted in the morning, but quickly spring back to life once they thaw).

Plants also produce cold-tolerance proteins and sugars (their own natural antifreeze), which act to lower the freezing point of water inside plant cells and inhibit the growth of ice crystals. (This is why certain vegetables end up tasting sweeter if they’re harvested after a few frosts.)

They’ll even change the composition of fats in their cell membranes, giving them a little more flexibility should any ice crystals form. If the plants are well-hardened, they can survive extremely cold temperatures. (Here’s some data on what temps will kill vegetable crops in my own garden.)

Warm-season crops like tomatoes and peppers don’t have these adaptations, which is why they turn to mush after a freeze. It’s a result of their plant cells bursting as water expands, kind of like a water bottle bursting in the freezer.

What really injures plants in winter

So if cold-tolerant plants can adapt to freezing conditions, what actually damages them? In most of the United States, it’s simply desiccation: the drying effects of cold winter winds. These plants have already moved water out of their cells, then the low humidity and harsh winds of winter dry out their tissues even further.

Early freeze damage typically shows up first on the leaf margins, producing tip burn, or dried crispy edges. And cold-tolerant plants don’t turn to mush when exposed to extreme cold; they simply look dehydrated or brown. So it’s really desiccation—not cold temperatures per se—that frequently damages plants.

Here’s a mature chard plant in my garden, planted in the open, showing tip burn after multiple clear nights below freezing temperatures.

On the other hand, these young chard plants suffered no damage, thanks to an insulating layer of snow.

The exposed outer leaves on this red-veined sorrel became dehydrated after several nights below freezing, while the protected inner leaves are still green and fresh.

Give protection by freeze-wrapping your garden

With that bit of understanding of how winter actually injures plants, it’s not hard to see how you can cheat the weather. You can push the minimum limits of those frost-tolerance tables simply by giving your plants some protection, either in low tunnels (what I personally use) or cold frames.

Read more: Low tunnels vs. cold frames—what’s more effective for winter protection?

It’s easy to think that these structures work by trapping some heat from sunlight during the day and releasing it at night, but there’s so much more to them than that. Think of it like freeze-wrapping your garden.

Disclosure: If you shop from my article or make a purchase through one of my links, I may receive commissions on some of the products I recommend.

In your freezer, freezer burn occurs due to the sublimation of frozen water from the tissues of meats and vegetables. You can prevent this by increasing the humidity in your freezer (which is hard to do), encasing your foods in frozen water, or more commonly, by making sure you have an airtight seal in the packaging around your foods. (I use and recommend this vacuum sealer for long-term storage in the freezer.)

You can mimic this freeze-wrap concept by “packaging” your garden beds into low tunnels or cold frames, which increases the humidity inside the structure (reducing sublimation of water from plant tissues) and protects the plants from drying winds—much in the same way that a good snowfall can insulate plants.

If you’re able to water your garden beds before an expected cold snap, that helps as well. The moisture further raises humidity inside the tunnel and moist soil protects plant roots from drying out.

So, how well does this work? A few winters ago, I had multiple beds planted with several varieties of leaf lettuce. Some were grown out in the open and some were grown under midweight frost cloth (also known as row cover).

According to the frost-tolerance table I shared above, lettuce should die at temperatures below 28°F and yes, some of the ones without protection did. (This is highly dependent on size and cultivar; generally, smaller plants fare better than larger plants and heat-tolerant lettuces are also more cold-tolerant, as contradictory as that sounds.)

But, all the lettuces in the low tunnels easily survived temperatures in the upper teens Fahrenheit.

The real test came when I saw a freak single-digit night of 2°F in the forecast and decided to throw an extra layer of fabric over my tunnels, just in case. The lettuces turned a bit limp (and some of them had leaf burn) but they survived.

So how cold did it get inside the tunnels? I had a temperature sensor in one of those double-insulated tunnels and it got down to 14°F in there. (From personal experience, I’ve found that medium-weight frost covers like Agribon AG-30 provide around 5° of cold protection.)

So, temperature clearly isn’t the only factor that determines whether a crop will survive winter. (These are the sensors I use throughout my garden to monitor temps and humidity.)

Recommended

Frost protection for plants

Don’t baby your plants

If you want to give winter gardening a shot with these cold-protection tricks, don’t baby them. Just as the cellular changes and sugars they accumulate are induced by cold weather, they’re quickly lost when the plants are exposed to heat.

That means you do need to pay attention to what the weather is doing. Frost cloth is a great option if you prefer to be more hands-free, since cold frames and tunnels covered in plastic need to be vented when temperatures rise to 40°F or above.

On a sunny 40°F winter day, the temperature inside a cold frame or plastic-covered tunnel can easily reach 80°F or more, which causes plants to lose the sugars and antifreeze proteins they’ll need to survive when temperatures plunge at sundown. If you use plastic covers, invest in a temperature sensor and be sure to vent your tunnel if it approaches 60°F inside the tunnel.

(If you can’t decide what kind of cover to get for your low tunnel, I’ve got a guide that compares fabric vs. plastic row covers and when you’d want to use one over the other.)

In my years of gardening in the Central Oregon high desert and harvesting leafy greens all winter, I’m convinced that keeping cool-season plants cool—what they’re naturally adapted for—is the key to successful winter gardening.

For ideas on what you can grow all winter, bookmark my guides on cold-hardy vegetable crops and cold-hardy herbs that can survive a hard frost.

An excellent treatment. I have a few candidates to add.

• Variety: “Yellow Heart Winter Choy” ( is an extremely cold tolerant Asian brassica offered by Baker Creek seeds. (open pollinated) So far, there ia no postage & handling charge when ordering from them online (www.rareseeds.com), so buying even one packet is economical. I also use them if I need to fill in for one variety (for example if I order something from another supplier who sells out that variety, I can inexpensively fill in from Baker Creek.

• Variety: “Joi Choi” pac choi. (hybrid) Hands down the best pac choi I have grown, producing in heat as well cold. Also, I have found it to be the best pac choi for planting a bed thickly and thinning over and over as the plants get bigger. So long as it can keep growing, it never gets tough or bitter. In Florida I had plants grow to at least 2 feet in diameter, remaining crisp & tender. Of course if one wants to save seed, an open pollinated variety is called for

• Strategy: A hot bed can be easily constructed to provide bottom heat for plants even in sub-zero weather. The best hot bed heating material, hands down, is horse manure (preferably with bedding), which was used for hot beds by generations of gardeners and farmers when horses provided most transportation and traction work. (I think going back to horses instead of tractors, etc., would be a good move…no fossil fuels or rare earth elements requires.) Riding stables and stables that rent shelter privately for owned horses need stables cleaned. We have gotten a lot of horse manure by swapping stable cleaning for taking what we removed. A hot bed can also be built with leaves raked in the fall (again usually free for the taking.) Best if shredded a bit. Mix in human urine and cover with 6 inches or so of topsoil (important for any hotbed heating system. Typically, a hot bed will generate a useful amount of heat for about 6 weeks, so you want empty beds on standby to provide entire winter gardening in long-winter climates. The best hot beds are at least 18 inches (2 feet are better) deep. The bed should be covered with some sort of glazing. My grandfather wrote a paper on hot beds in the early 1900’s, recommending cheese cloth as glazing. The country had just gone through a depressing and WW I, and glass was dear. G;as is best. Standard cold frames can be used, though they probably will require excavation to make room for the manure.

• Grow frames. Grow frames are essentially small greenhouses. Conventional and solar greenhouses provide room for the gardener. Grow frames just allow room for the plants. Typically, they require manual venting on sunny days, even in sub-zero weather. And if it snows overnight, the glazing needs to be swept. So this is not for an old person such as myself, or for someone whose schedule would not allow a random outdoor chore.

• Attached greenhouses. These are obviously a bigger investment, but they can be elegant living space as well as, in many cases, almost all of the winter home heating. Avoid designs that involve air circulation through tubes imbeded in rock, earth or concrete, as these invariably result in mold growth with the spores actively circulated through the house and attached greenhouse. Again, attend to venting, even in extremely cold weather. (Relatively inexpensive vent opener/closer devices requiring no electricity are available.) And read up on biological pest control for greenhouses. It can be done; I’ve done it successfully in every greenhouse I’ve managed. (Predatory and parasitic insects are the core of the pest control strategy.) I’ve been in an attached solar greenhouse in New Hampshire that was being studied for its contribution to heating the home. Passive solar was providing more than 90% of the heat. That would require a lot of photovoltaic cells, there would be no other benefit (food, enhanced living conditions, aroma from plants such as lemon trees, etc.) The glass will last indefinitely unless broken. requires no rare earth or lithium, and unlike PV, will never need replacement. (Other kinds of glazing do have a limited life span.) Always use tempered glass where people will sometimes be under it. A panel of low-iron glass where seedlings will be germinated goes a long way in preventing die-off. (Low-iron glass passes UV light that kills damp off.)

The the more food we grow ourselves and the more of the year we do it, the more food-secure we will be against the failure of entire agricultural regions due to climate change. This will happen because we, humans, have not invested enough in converting our lifestyles to minimize our individual and collective contributions to ‘greenhouse gases’.

I learned the hard way that mulch does not protect herbaceous plants, but actually can increase the degree of damage. I convinced my elderly to fill his pickup with seaweed that had washed onto a public beach after a storm. (Removing seaweed from other shoreline situations is a no-no. It is essential as a part of coastal ecosystems). I recommend that he mulch his fall broccoli plants. Soon there was a hard freeze. The mulched broccoli plants were damaged but the unmulched plants in the same row were unaffected. Apparently, the mulch insulated the soil, which otherwise would radiate infrared that produces warmth when it is absorbed. I’ve read that in dry deserts, where rain, when it comes, is brief and light, mulch should be avoided. It absorbs the rain water which soon evaporates. After 3/4 century of gardening, I’v concluded that general rules should be intelligently analyzed for why the work. Nature has no hard and fast rules, other that that all vascular life dies and all species go extinct.

One other frost related tip: I worked a few years as co-director of a CETA (federal funded jobs program) youth gardening project: we taught various organic techniques, including winter gardening where the night temperature could sometimes settle at 120* for a few hours. (A guy named Steve Tracy started the program for conventions/solar gardening as a town-based program. He recruited me when the fed program funds were available.) One feature of the program was teaching kids to build solar pods using a design a design developed buy a guy in New Hampshire.). The pod walls were constructed using two depths of 2×12 lumber with 2″ foam insulation. The foam was covered with sheet metal to retard deterioration an make things diffulct for mice looking to burrow into them for a snug winter. Steve also had gotten funding to research the efficacy of the pods for winter growing. He ran into two puzzling situations that I was able to explain, one of which I’ll treat here because it relates to this post. In freezing weather, sometimes leaf crops that were mature, essentially covering all the soil, were nipped by frost while immature plants were fine. This was the same issue as the seaweed mulch an broccoli above. Chlorphyll effeciently reflects infrared radiation, so the radiation from the soil was thwarted from protection all but the bottom leaves. Harvesting alternate mature plants would probably have been enough to save those remaining in the pod. I organized using one of our pods as a hot-bed, 6″ of soil over a foot and a half of horse manure. One of the kids set out a tomato plant in about January or February. That winter had extremely hard freezes but the plant survived until someone forgot to close the pod in may. (Even in sever cold, the pods can overheat in bright sun if not ventillated a bit.)

Which cover do you prefer for lettuce, plastic sheeting or frost cloth for a more hands-free winter gardening?

It really depends on your climate and garden orientation. Personally, I grow lettuce under frost cloth because we do get lots of direct sun all day and winter temps that can climb into the 40s or 50s Fahrenheit, and I can’t always get out there to vent a plastic cover.

Fascinating discussion on growing vegetables in the winter. I have a question, will the vegetables survive if temperatures stay below -10C /14F throughout the day as I live in a zone 3 climate category.

Yes, if you grow cold-hardy vegetables and keep them mulched and covered. In my climate, we’ve had days where the temps never got above 20F all day (with lows in the single digits). One of the things that helps is making sure your soil is adequately moist before a cold spell like that. If it hasn’t rained or snowed in a while, your plants will suffer in winter.

lots of ideas to try. use up old seed packets of greens and experiment. one missing from the list is my all time favourite, named claytonia or winter purslane or miners lettuce. we eat it raw in salads or smoothies, use the whole plant as a puree cooked gently with garlic and cream or in stir fry. It appears everywhere in the poly tunnel around the beginning of November and keeps going until end March or later. self seeds but is not invasive as very easy to pull up. have to watch for slugs.

I have it as miner’s lettuce on the list in the far right column, and yes I love it as a hardy winter green! That and mache will grow all winter for me.