The first time I saw cucamelons in a seed catalog, I was smitten. I found them in the “cucumber” section and as I usually try to grow at least one novel cucumber variety per season (like the cream-colored orbs of Dragon’s Eggs or the slender and striated Metki Painted Serpents), I promptly bought a packet and have been growing them ever since—going on 10 years now.

The novelty hasn’t worn off—in fact, our household (which expanded by two kids in that time) has only loved them more and we look forward to picking them in the garden every summer.

They’re incredibly easy to grow, with vines that go gangbusters given proper conditions. And you should definitely grow these, as I’ve seen cucamelons fetch a pretty penny at farmers’ markets!

If you got your hands on some seeds or starter plants, here’s everything you need to know about growing cucamelons (plus tips for saving the tubers so you can grow them again next year).

| Scientific name | Melothria scabra |

| Common names | Cucamelon, mouse melon, Mexican sour gherkin, Mexican sour cucumber |

| Life cycle | Tender perennial |

| Hardiness | USDA zones 7+ as a perennial |

| Days to maturity | 65 to 75 days |

| Mature size | Vines up to 10 feet long, fruit up to 1 inch long |

Disclosure: If you shop from my article or make a purchase through one of my links, I may receive commissions on some of the products I recommend.

What is a cucamelon?

Looking like lilliputian watermelons with their distinctive dark and light green “rinds,” cucamelons make up in character what they lack in size. The cucamelon (Melothria scabra) is an heirloom vegetable native to Mexico and Central America, where it’s known as sandía ratón (“mouse melon”) or sandita (little watermelon).

Here in North America, these grape-sized fruits are sometimes called mouse melons, Mexican sour gherkins, or Mexican sour cucumbers, but the taste is neither sour nor watermelon-y. I’d say the flavor is more of a pleasant tartness, like cucumber with a twist of lemon. A cucamelon, if you will.

Where to buy

Cucamelon seeds

Cucamelons have been around since pre-Columbian times, but were not brought into botanical classification until the mid-1800s.

Despite being a member of the Cucurbitaceae family (and often lumped together with other cucumbers in seed catalogs), cucamelons are part of an entirely different genus of plants and are only distantly related to cucumbers, so they will not cross with other cucumber varieties.

They’re also more cold-tolerant than cukes, and will continue to fruit until the first frost.

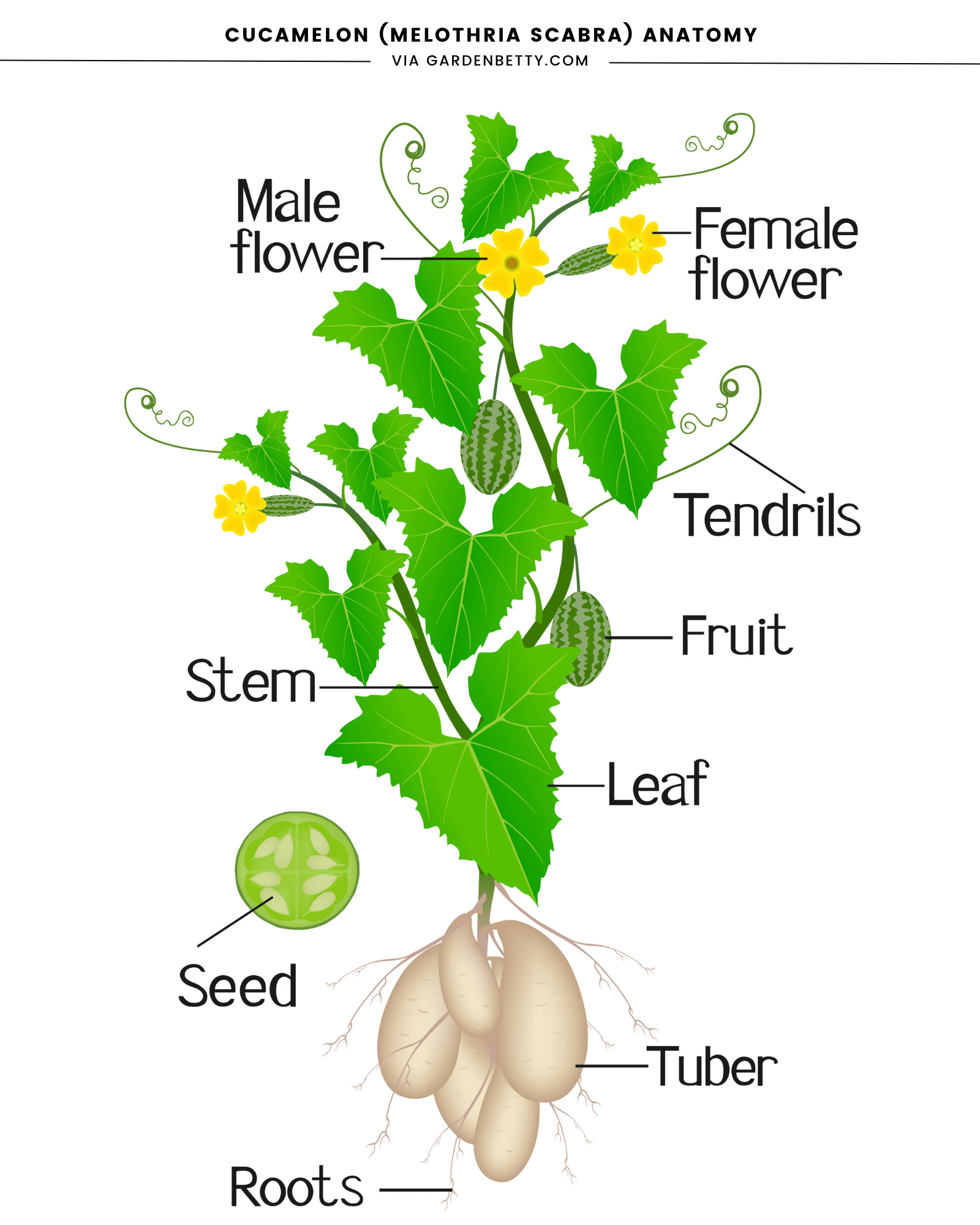

Cucamelons grow on thin, sprawling vines that are more delicate than those of typical cucumbers, but don’t be fooled—these are big plants! The vines can reach up to 10 feet if planted in the ground (or around 5 feet in a large pot), with lots of little tendrils that love to climb a trellis (and you’ll definitely want to train them, as the vines get tangled up pretty easily).

Each plant has both male and female flowers; the latter is pollinated by wind or insects. The plant is so prolific that it can produce close to a hundred fruits in a single season, peeking out from between ivy-shaped leaves.

Open up a cucamelon and you’ll find pale green flesh with soft white seeds that are edible. The whole thing is crisp and juicy and totally snackable on the go!

It’s possible to overwinter a cucamelon plant

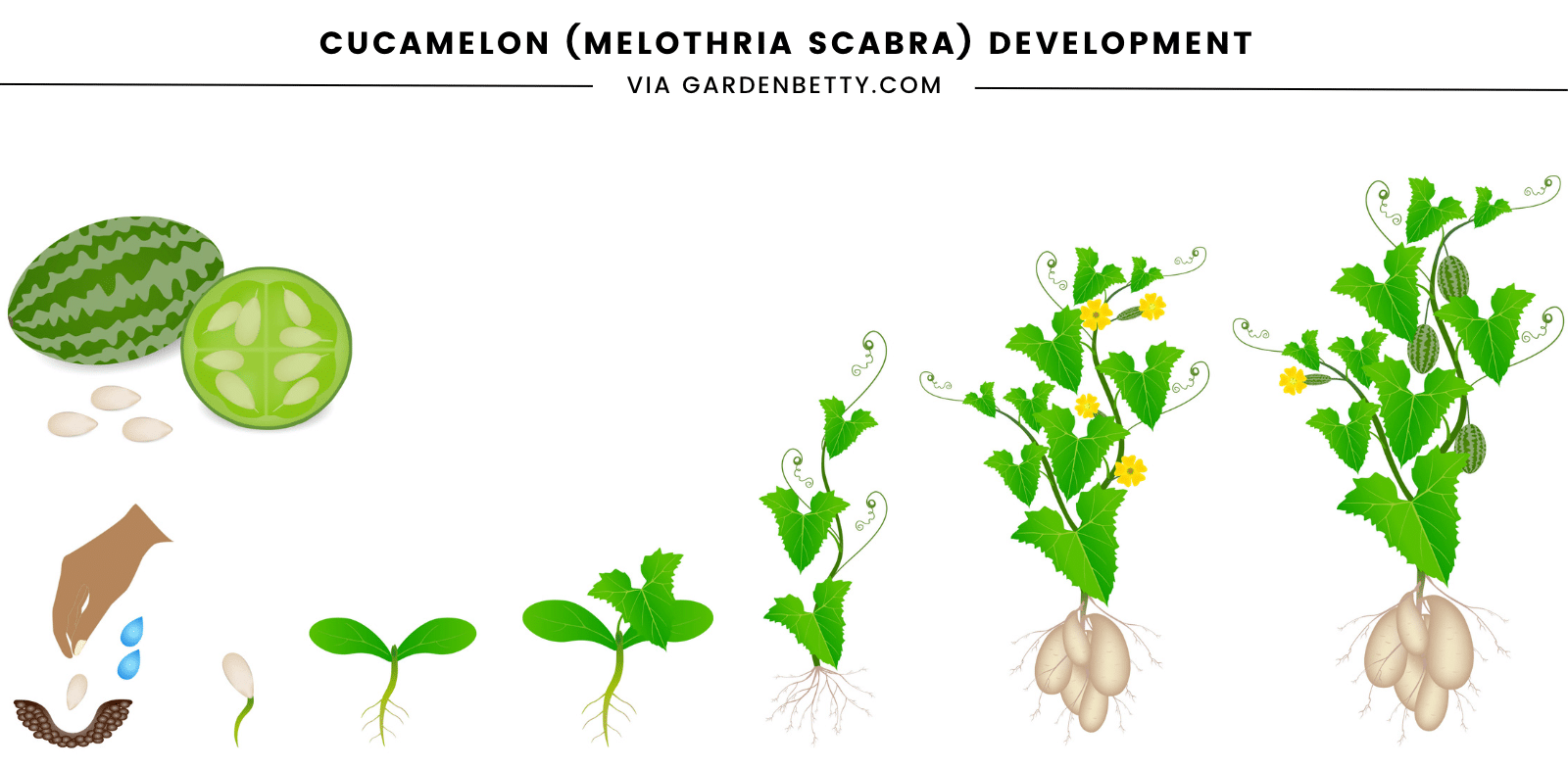

Before I get into growing cucamelons at home, you should first understand how they grow.

Most people grow cucamelons as an annual, but in fact, Melothria scabra is a tender perennial. It thrives in warm weather and will grow during cool spring days, but temperatures below 60°F will significantly slow down growth.

Over the course of a season, the plant develops fleshy white tubers underground that grow 4 to 6 inches long. Each plant can yield several good-sized tubers.

As winter approaches, the leaves may die back but the plant will emerge anew in spring from these tubers. In USDA hardiness zones 10 and 11, you don’t need to do anything but trim any tired-looking foliage.

In zones 7 to 9 where cucamelons are more susceptible to cold weather, you can overwinter a cucamelon plant by cutting back the dead foliage and adding a deep mulch layer of at least 12 inches to protect the tubers underground (shredded leaves or straw work well).

In zones where the soil freezes (like where I live in Central Oregon, zone 6b), you can dig up the tubers and store them the same way you’d store dahlia tubers. (Keep reading to learn how to grow cucamelons from tubers you’ve saved.)

Growing cucamelons from seed

Cucamelons grow easily from seed, and the method is not unlike growing cucumbers. They like full sun to partial shade, and require rich, well-draining soil amended with compost.

If you’re in zones 3 to 6, you’ll want to start seeds indoors about six weeks before your last spring frost. The seeds are tiny, so only sow them about 1/4 inch deep and keep the soil consistently moist so the seeds don’t dry out. They will germinate in 7 to 14 days.

Read more: Find your first and last frost dates with this customized planting calendar

Like other members of the cucurbit family, cucamelons don’t always respond well to transplanting. If you have the space, I recommend sowing seeds in 4-inch pots and thinning to the strongest seedling per pot, which helps them develop good root systems and minimizes transplant shock.

You might even want to insert a chopstick—like the disposable ones you get with takeout food—so the seedlings have something to climb. This keeps them from getting tangled together in your seed starting trays.

Once all risk of frost has passed, harden off the young plants and move them into the garden, giving them 12 inches of spacing.

It’s tempting to plant them closer when they’re small, but you’ll only set them back. These are large plants with deep root systems! A 12-inch spacing gives the tubers room to grow (and keeps the vines from getting too dense and tangled up).

Related: How to find the root depth of garden vegetables

In zones 7 and up, you can sow seeds directly in the garden in spring around the same time you sow cucumber seeds. Sow seeds every 4 to 6 inches and thin the plants to a final spacing of 12 inches.

A few weeks after cucamelons sprout, they’ll turn into vigorous vines that need a trellis or fence to climb. I like to use twine, netting, or cattle panels and train the vines up and over as they grow—I’ve had trailing vines as long as 8 to 10 feet!

Digging up and storing cucamelon tubers

Cucamelons are heat-loving, frost-sensitive plants and won’t survive temperatures below 50°F for very long. After the leaves have died back, cut them down—you definitely don’t want to yank out the tubers by pulling on the vines, as this usually results in damaged tubers that aren’t likely to overwinter.

Dig a garden fork or shovel about a foot away from the main stem of the plant and lift the soil to expose any tubers. If you don’t see tubers, dig a little deeper or use your hands to root around for them.

Once you’ve collected all the tubers, store them in a large container filled with moist (but not wet) potting soil in a cool, sheltered spot that won’t freeze, like a garage, an unheated basement, or a moderately heated greenhouse that stays between 40°F and 50°F.

This is how I’ve stored cucamelon tubers successfully over winter:

- Add water to a tub of potting soil until it reaches a consistency of damp sand.

- Fill a large-diameter plastic pot or Gorilla Tub with about 3 inches of this pre-moistened soil.

- Place a few tubers on the soil in a single layer so they’re barely touching.

- Add another few inches of soil on top followed by another layer of tubers, and keep going until you run out of space (or tubers).

- Cover the last (top) layer of tubers with more soil, and store in a cool, dark place.

Growing cucamelons from tubers

Did you save cucamelon tubers from your last harvest? Way to go—growing cucamelons from tubers gives you a head start on the season and results in an earlier and larger harvest.

About eight weeks before your last expected spring frost, pull the tubers out of storage and separate them.

Plant each tuber in a 2-gallon pot filled with potting soil (the tuber should be about 1 inch below the surface). Move all of your pots to a sunny window or under grow lights, water well, and keep the soil moist as the plants start growing again.

Once all risk of frost has passed, harden off the plants and transplant them in the garden.

How to harvest and eat cucamelons

Cucamelon plants begin to flower about 60 days after planting, and it takes another 7 to 10 days after pollination for the fruits to become large enough to harvest.

Growing from teeny tiny blossoms, they never get more than an inch or so long and tend to drop from the vines as soon as they’re ripe (but it’s easiest to pick them before they drop so you’re not hunting for dozens of cucamelons on the ground).

In my opinion, cucamelons are best eaten raw and eaten whole. They make the perfect palm-sized snack while you’re working in the garden, but if any of them actually make it back into your kitchen, they’re delectable in salads, crudité platters, or charcuterie boards as a palate cleanser (and are a great conversation starter if you’re serving guests).

Because the flavor and texture reminds me of cucumbers, I think cucamelons are a natural choice for pickling—which makes sense when you think about its other moniker, Mexican sour gherkin. (A gherkin is a cucumber that’s been pickled.)

You can see Mexican sour gherkins used here in my recipe for Bread and Butter Pickles, but their crunch holds up well in other quick-pickle brines too. (Try the brines in my other recipes for Pickled Radish Seed Pods, Fiesta Peppers, and Sriracha Stem Pickles.)

Cucamelons also work well in cocktails, particularly gin cocktails like this one, garden-inspired tequila cocktails like this one with shiso herb, or refreshing botanical margaritas like this one.

You can also cook cucamelons, but heat tends to mellow out their distinctive tartness and make them taste more like zucchini.

If you want to try them in a stir-fry, toss the cucamelons in toward the end and cook for just a couple of minutes. They add just the right amount of crispness to a noodle or rice bowl!

Saving cucamelon seeds

If digging and storing the tubers is too much effort, you can save seeds from ripe cucamelon fruit to propagate next year’s plants.

Cucamelon seeds are encased in a gel-like pulp. To save them, cut the cucamelon in half and remove the seeds. Try to separate the seeds from as much of the pulp as possible.

Place the cucamelon seeds in a glass of water and leave them for two to three days. During this time, you should see a cloudy white film develop on the surface; this film is just harmless kahm yeast, which indicates lacto-fermentation in action.

Once the film has covered the entire surface, strain and rinse the seeds in a fine-mesh strainer. Lay the seeds out to dry on a plate or towel, then store in a labeled and dated envelope in a cool, dry place.

Similar to fermenting tomato seeds, fermenting cucamelon seeds helps them germinate quicker by removing the germination-inhibiting substance on the seed coat. It’s a simple extra step when saving seeds, but worth it if you want to increase your chances of quick germination in spring.

Melothria in the wild

The cucamelon is similar in size and appearance to another vining perennial plant, Melothria pendula (also known as creeping cucumber or Guadeloupe cucumber).

This wild species is found from Pennsylvania to Florida and west to Texas and Nebraska, as well as its native Mexico and Central America, where it grows along the edges of marshes, sandy roadsides, forests, ditches, and ravines.

But is Melothria pendula edible? This source (and several online wildflower databases) claims it is, as long as you consume only the light green fruits (which share the same slightly tart flavor of Melothria scabra).

Unlike Melothria scabra, however, the fruits on the wild Melothria pendula gradually darken as they ripen, going from dark green to purple to black (at which point it’s said the fruits are rather foul-tasting).

If you find Melothria pendula growing wild in your yard, it’s definitely worth trying a few light green fruits from this edible weed!

Read next: More edible weeds that are actually delicious

This post updated from an article that originally appeared on September 22, 2012.

Right here: https://gardenbetty.com/african-blue-basil/

I’ve got the wild cucamelon growing all over my yard in Zone 8b. With nothing to climb, it acts like a ground cover, but I want to keep it away from my garden. When I pull it, I don’t see tubers like in your image, but rather thick roots that look kind of like La Choy chow mein noodles. I’ve wondered if these roots are edible. Do you know?

If you’re referring to Melothria pendula, I’m unsure if the roots are edible.

THanks so much for this interesting post! I love your newsletter. Every year I plant cucumbers and every year they are attacked by pests. I’m thrilled to read about cucamelons, and wonder if they are more pest resistant than regular cukes. Do you know? Thanks! Susan

This is tricky, since cucurbits generally attract the same pests (for example, you’ll sometimes find cucumber beetles on squash plants). That said, planting a different member of the cucurbit family, and planting it in a different spot away from other cucurbits, may yield better results. Good luck!

I am so glad I happened on this entry about cucamelons. In the last few years, I’ve had what I thought were cucamelons springing up all over the back yard, but I wasn’t sure. I’m in the Southeast, and now I know that the plants are the native Melothria pendula. I’m glad to know the fruit is edible. Wikipedia has an entry on this plant stating all parts but the fruit are of “unknown toxicity.” The ripe black fruit is said to be “highly laxative.” I think I’ll try pickling some of the green fruits.

I wasn’t sure if I was going to grow them again this year! But you’ve convinced me, and perhaps I’ll even try to overwinter them. I’m in Zone 5 so it’s COLD! hahaha. They’re such a great snack and salad addition.

I can’t find anything about how much sun this vine can take. I live an hour north of Mexican border so I’m assuming my weather is right for this, but I can’t find anything specific.

My seed packet says full sun. I’m up north, so mine are growing under LED shop lights in one space and in a pop-up greenhouse. Those in the greenhouse are getting a lot of sun and are growing well.

We planted these this year for the first time. We didn’t use a trellis to start with and they started to take over the whole yard! Definitely know better for next year. 😉

For being such prolific plants, their leaves are deceptively small compared to other cucumbers!

I want to grow these! How many seeds did you plant? Approximately how many gherkins grew on one vine? Thanks.

I sowed one seed every 3-4 inches and probably had a 4-foot row. I’m not really sure how many gherkins grow per vine, dozens? I had several plants going up a trellis so I harvested a lot!

Hi am Giannis Doskaris from Greece. I would to ask what is the harvest of the vine? What is the taste?

It tastes like a tart cucumber. See post above! ^

Love these! I got the plants from The Drunken Botanist seed collection at Territorial Seed Company- and they are the first vines of Any kind that have ever done well in our so. WV garden!! They are adorable, too! I’m about to pickle 100+ of them so we can throw them in cocktails instead of olives or onions! 🙂

Our vine is growing madly and lots of tiny fruit. How will I know when they are ripe?

If they fall off the vine easily, they’re ripe. Mine have never grown to be more than an inch long.

these are cool, I read this post back last year but the cucamelons weren’t available in the UK then – they’re all over the news now AND I can finally buy the seeds! from this site: http://www.suttons.co.uk/

I live in North Dakota and like the fact that these little guys can handle some coolness. I would LOVE to plant some of these but have mnever seen or heard of anything like them. Do you know where I could possibly order seed for these ffrom some place????? Sure would appreciate any help you could offer me. I love to can, love your site, stumbled on it by accident. But got you on Pinterest now!!!!!!!!!!!!

Thanks for the love! My seeds came from http://rareseeds.com.

I got my plants from the Drunken Botanist Seed Collection at Territorial Seed Company and they did Great- THE first cucumber/squash/melon vine of Any kind that’s done well in our so. WV garden!

Got my seeds from Amazon

Interesting (here via Small Measure) cucumbers. We have a smaller, similar, native Melothria pendula but I’m not sure it is edible. Will have to investigate these a bit more! (love your blog so far!)

Thank you Misti! Please do stick around!

It’s my first year growing them and I am hooked! I’ll definitely be giving them a prime spot in the garden next year as my harvest was really measly this time.

Love the look of these and imaging the taste. did you grown the vine from seeds or transplant. I bought a transplant and it grew all over the fence but the little blossoms never developed any further.