“How do you keep a vegetable garden going all winter?”

It’s a question I’m often asked in my zone 5 microclimate because I harvest leafy greens all winter long without a greenhouse. Choosing the right cool-season crop is important, of course. As is mulch and a moderate frost blanket to warm my low tunnel by a few degrees.

But while cold temperatures do play a role in how much (or rather, how little) your crops grow, day length actually matters more.

Why?

Because while outdoor temperatures can be altered with greenhouses, cold frames, or low tunnels, we’re really at the mercy of day length when it comes to growing vegetables.

Read more: Why I prefer low tunnels over cold frames for winter protection

Most plants need at least 10 hours of light for active growth. When day length falls below this threshold in winter, plant growth slows to a crawl or even stops completely—even if temperatures are mild.

This period of reduced day light has been dubbed “Persephone Days” by winter garden guru Eliot Coleman. He named it after the Greek goddess of spring, Persephone, whose annual return to the Underworld caused the earth to go barren and brought about the change in seasons.

If your goal is a green and productive vegetable garden in winter, you can use Persephone Days to help you time your plantings from summer to fall so you can keep harvesting through the shortest days of the season.

Calculating your Persephone Days

Depending on where you are in the country, the period where there’s less than 10 hours of sunlight a day usually falls between November and February.

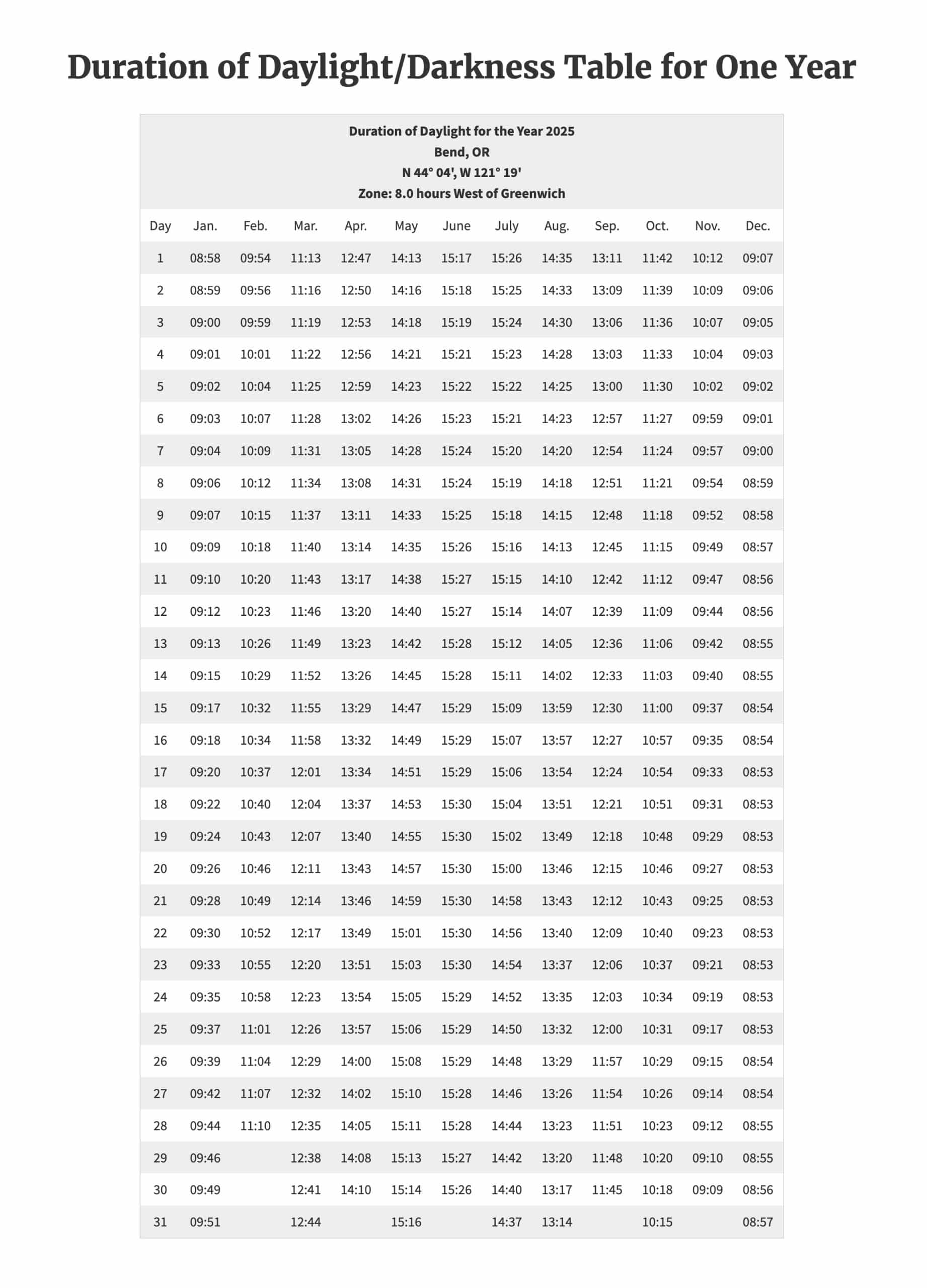

You can check the exact dates on the US Naval Observatory website, which has an online tool that retrieves a Duration of Daylight Table (like the one below) for any location in the US.

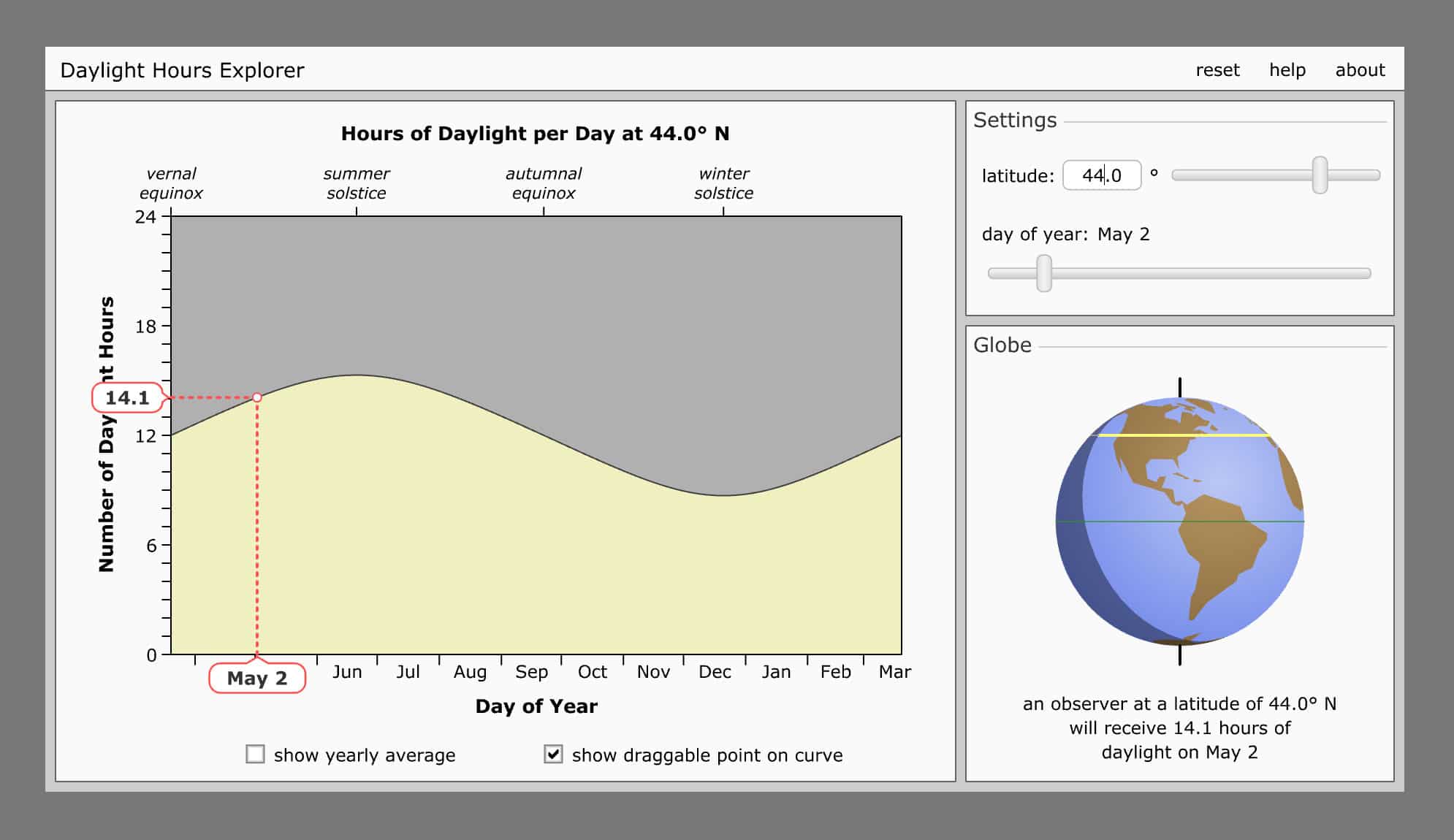

If you’re more visually inclined and know your latitude, the University of Nebraska-Lincoln has a neat little tool (example below) that lets you explore a graph of your location’s day length throughout the year.

At my latitude in Central Oregon, the Persephone Period begins the second week of November and ends the first week of February. That’s three solid months of minimal to no plant growth, yet I can keep picking salads until we finally see more sun in early February.

How is that possible? By working backwards from the Persephone Days.

Getting the timing right

In order to have a thriving winter vegetable garden, your plants need to be at least 75 percent mature by the time the Persephone Period starts. The farther along they are, the more you’ll be able to harvest.

Since most leafy crops take around 50 to 80 days to mature, the majority of gardeners should have the bulk of their planting done between mid-August and mid-September. This might seem late, especially when you account for cooler nighttime temperatures and waning sunlight, but remember that you’re planting a winter garden—and not planting for a fall harvest.

Related: These fast-growing crops can be planted in late summer for a fall harvest

Plant growth will slow as you approach the autumnal equinox, but it doesn’t stop completely, so your vegetables will continue to mature (albeit sloooowly) through early spring.

If you sow seeds by mid-September, you’ll generally have quick germination rates and steady growth, thanks to summer’s warmth and moderately long days. Any seedlings started indoors can be transplanted between now and early fall while the soil’s still warm.

Quick tip

If this is the hottest time of year for your area, here are a few tips on how to plant cool-weather crops in the heat of summer.

However, don’t feel discouraged if you’ve missed this “deadline.” I’ve scattered seeds for hardy arugula and Asian greens under my low tunnels as late as mid-October; while they only grow a few inches tall by late December, they provide delicious baby greens for my winter salads.

Once sunlight dips below 10 hours a day and your garden slows down or comes to a virtual standstill, it’s just a matter of protecting your plants from the elements. It’s like putting them on hold for the next four months in an outdoor “refrigerator,” but in the meantime, you can keep harvesting as needed.

The variety matters too

Choosing the right cool-season crop will make things much easier in the garden come wintertime.

Plants that are naturally winter-hardy will be less fussy about temperature. You don’t want to spend all your time coddling a plant that’s just barely able to survive your hardiness zone. You want a plant that will not only survive, but thrive in the cold, become more flavorful, and bounce back easily in spring.

Many types of vegetables do well in winter, even for us northern gardeners. I’ve written before about some of my favorite cold-hardy crops here, as well as crops that have a spectacular tolerance to frost and freezing temperatures. (You might be surprised to learn just how many are on that list!)

When you grow a variety that’s appropriate for your climate, you often don’t even need a greenhouse; simple plastic or fabric row covers are sufficient to protect your plants from cold, drying winds (which are far more damaging than frigid temperatures alone).

All of my winter vegetables tolerate lows down into the teens (Fahrenheit) with the occasional single-digit night, and all I use is one or two layers of midweight frost cloth. If your area gets consistent snow cover all winter, then you can even skip the fabric since snow insulates so well.

Getting a head start on spring

Knowing your Persephone Days can help you plan ahead for spring too.

Once day length increases to 10 hours in late winter, many zones can start sowing seeds outside for cold-hardy crops like peas, fava beans, salad greens, and root vegetables. (I’ve got a list here of other cool-season seeds you can plant before the last frost.)

In Central Oregon, I usually start seeds for the first round of mache, arugula, and spinach in my low tunnels around the second week of February, which is soon after the Persephone Period ends. All of these seeds will germinate in cooler soil temperatures, so it’s just a matter of protecting young seedlings from a hard freeze. (You can see a chart of other seeds’ minimum germination temps here.)

This is the same time some of my perennial crops (such as rhubarb, sea kale, sorrel, lovage, walking onions, and chives) begin to put out new shoots, and my overwintered kale and chard resume their growth. It’s so fun to watch the garden come alive and go through sudden growth spurts once the sun arcs higher on the horizon!