If you’ve been collecting houseplants for a while, you’ll know there’s a mind-boggling amount of different types of plants out there. There are tons of different species, but not just that—nurseries also selectively breed or cross plants to create even more new varieties.

Sometimes it feels like you have to be a horticultural scientist just to understand what kind of houseplant you’ve got on your windowsill.

To hopefully make things a little less confusing (and keep the info all in one easy place to reference), I’ve created this little guide to plant taxonomy.

Below, let’s have a look at:

- What constitutes a species

- The difference between varieties, cultivars, and nativars

- The concept of hybrid houseplants

And all those other terms you hear thrown around in the houseplant world!

Family, genus and species

When trying to make sense of the vast array of houseplants out there, one thing that helps is to understand how the different varieties came to be. Some are man-made, but others occur in nature.

I’ll start by explaining the structure for the latter, then we’ll move on to stuff that has been subject to some human meddling.

Scientists actually came up with a neat taxonomical (naming) system ages ago to make at least some sense of all the different plants and animals that occur in nature.

This standardized system, which you might know as “scientific naming” or “Latin names,” comes in quite handy for us houseplant enthusiasts. After all, if just anyone can make up a name for a plant, things quickly devolve into chaos.

Take houseplant common names, which can be wildly confusing.

The same name may be used for two totally different species, or alternatively, one species might go by six different nicknames. That’s when we use the scientific name, which leaves little doubt about which exact plant we’re talking about.

As an example, in this article, we’ll use the genus Philodendron. If you have any houseplant experience, you’re sure to have heard of this one: There are almost 500 species of Philo, many of which are popular worldwide for indoor growing.

Buckle up! This is a hierarchical system, so we’ll work from broad to narrow. Many names are in Latin, so don’t be confused if they sound like gibberish to you at first.

What is a plant family?

All of our plants form part of the kingdom Plantae (the plants, unsurprisingly).

They also belong to different clades (the flowering plants, the grasses) and orders, but these categories are so broad that you’ll rarely hear them referred to in the houseplant hobby.

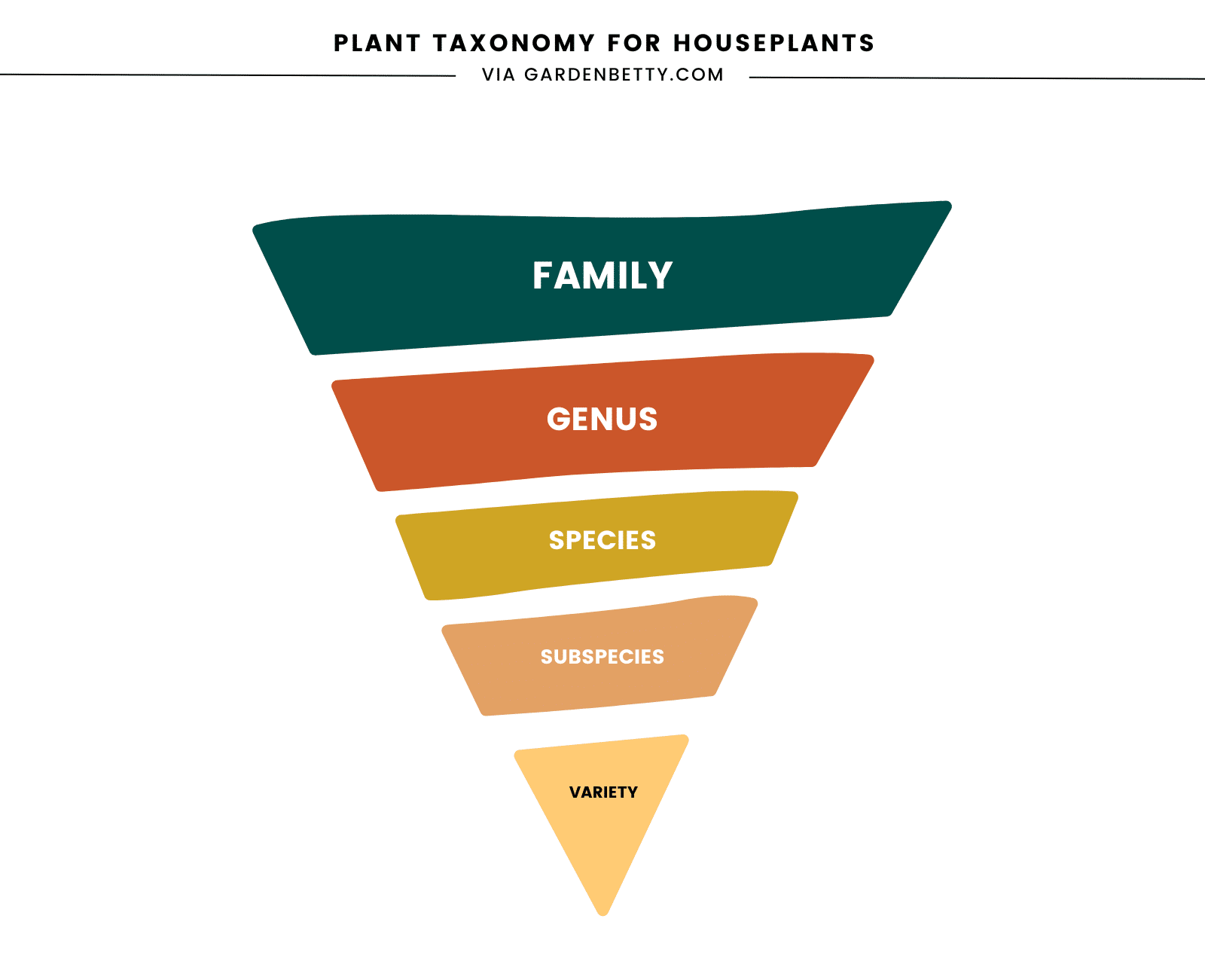

The first level in the biological taxonomy hierarchy that’s relevant to us casual houseplant collectors, and which you’ll often hear folks refer to, is family.

Our example plant, Philodendron, forms part of the family Araceae, also known as the Aroids. There are about 4,000 species of Aroids, many of which are popular as houseplants. There’s our Philos, but also Anthurium, Alocasia, and many more that you might recognize.

The taxonomical concept of family is handy because it helps categorize plants that are thought to have a common ancestor, and that therefore have certain characteristics in common.

In the case of the Aroids, they all have similar flowers, for example. Most are tropicals, meaning they tend to require roughly the same care.

There are many more large plant families that contain classic houseplant favorites. Take the Cactaceae, which includes all types of cacti. Or the Orchidaceae, which—you guessed it—houses the orchids.

What is a genus?

Plant families are made up of different genera (singular: genus).

A genus, in turn, contains different species that are particularly closely related, sharing a common lineage and many visual and physical characteristics.

Can you see the hierarchy starting to form? It’s hopefully clear by now how this all comes in handy for identification and classification purposes.

In the case of the Aroids, Philodendron is one of the 140 or so genera that make up the family. The other plants I mentioned earlier, Anthurium and Alocasia, are two other examples of genera in the family Araceae.

The genus Philodendron is a particularly large genus of plants, as it has hundreds of members. This isn’t always the case.

Some genera contain only a handful of species, or even just a single one! This is called a monotypic genus.

In the Araceae family, the popular houseplant Zamioculcas zamiifolia (ZZ plant) is a good example. The genus Zamioculcas is monotypic, with Z. zamiifolia being its only member. There’s just nothing else like it, so it has the entire genus to itself.

Keep in mind that plants can be moved to a different genus if it’s discovered it makes for a better fit, often as the result of genetic testing. In some cases, scientists even create new genera or retire a genus if they realize the previously assumed structure wasn’t quite correct.

Did you know? Species within a genus can often, though not always, interbreed. The offspring will have genes of both parent species, which can lead to a mixed appearance. We’ll discuss this further in the section on hybrid houseplants.

What is a species?

I’ve mentioned species already: they’re what make up a genus.

Species are very closely related, with the plants within them generally looking (almost) identical. They can reproduce together and, in the case of houseplants, their care requirements pretty much always apply to the species as a whole.

Now that we’ve gathered genus and species, we can correctly write a plant’s scientific name. It goes like this: Genus species. In the case of our Philos, the genus is Philodendron, which is always capitalized.

As I mentioned earlier, there are almost 500 species of Philodendron within the genus.

One example often grown as a houseplant would be Philodendron gloriosum, which is naturally found in Colombia and favored for its velvety leaves. “Gloriosum” is the species designation, which is never capitalized when writing the name.

Did you know? For the sake of brevity, it’s allowed to shorten the written notation for the genus name. This comes in handy if you’re listing a whole bunch of species within a genus, for example. For Philodendron gloriosum, you’d simply turn it into P. gloriosum.

What is a subspecies?

Given enough time, plants that belong to the same species might diverge a little.

In many cases, this is because they naturally occur in a different area and therefore eventually evolve some characteristics that help them adapt to their specific growing zone. Still, they’re not different enough to warrant the creation of a new species.

The scientific name for a subspecies is as follow: Genus species subsp. subspecies. I’m actually not aware of any Philodendrons that have subspecies, but in some other plant genera, it’s common.

The African violet is an example of a genus that has multiple species, many of which in turn have multiple subspecies.

An example of one of the species would be Streptocarpus ionanthus, often known as the “original” African violet. One of its subspecies is Streptocarpus ionanthus subsp. grandifolius, a name that suggests this one has evolved to grow bigger leaves than the original!

What is a variety?

I promise we’ve reached the last step of our scientific plant taxonomy journey here!

A plant variety is similar to a subspecies, but the differences tend to be a bit more minor. As such, they don’t warrant the creation of a full subspecies.

The correct written notation for a variety within a species is as follows: Genus species var. variety.

In the genus Philodendron, one example of a popular houseplant species that has different varieties is Philodendron hederaceum. It has three:

- Philodendron hederaceum var. hederaceum: Reddish-green leaves with a velvety texture.

- Philodendron hederaceum var. oxycardium: Slightly larger, glossier leaves that lack the reddish coloration.

- Philodendron hederaceum var. kirkbridei: Naturally occurs at higher altitudes and has slightly ribbed stems.

Cultivars, nativars, and hybrids

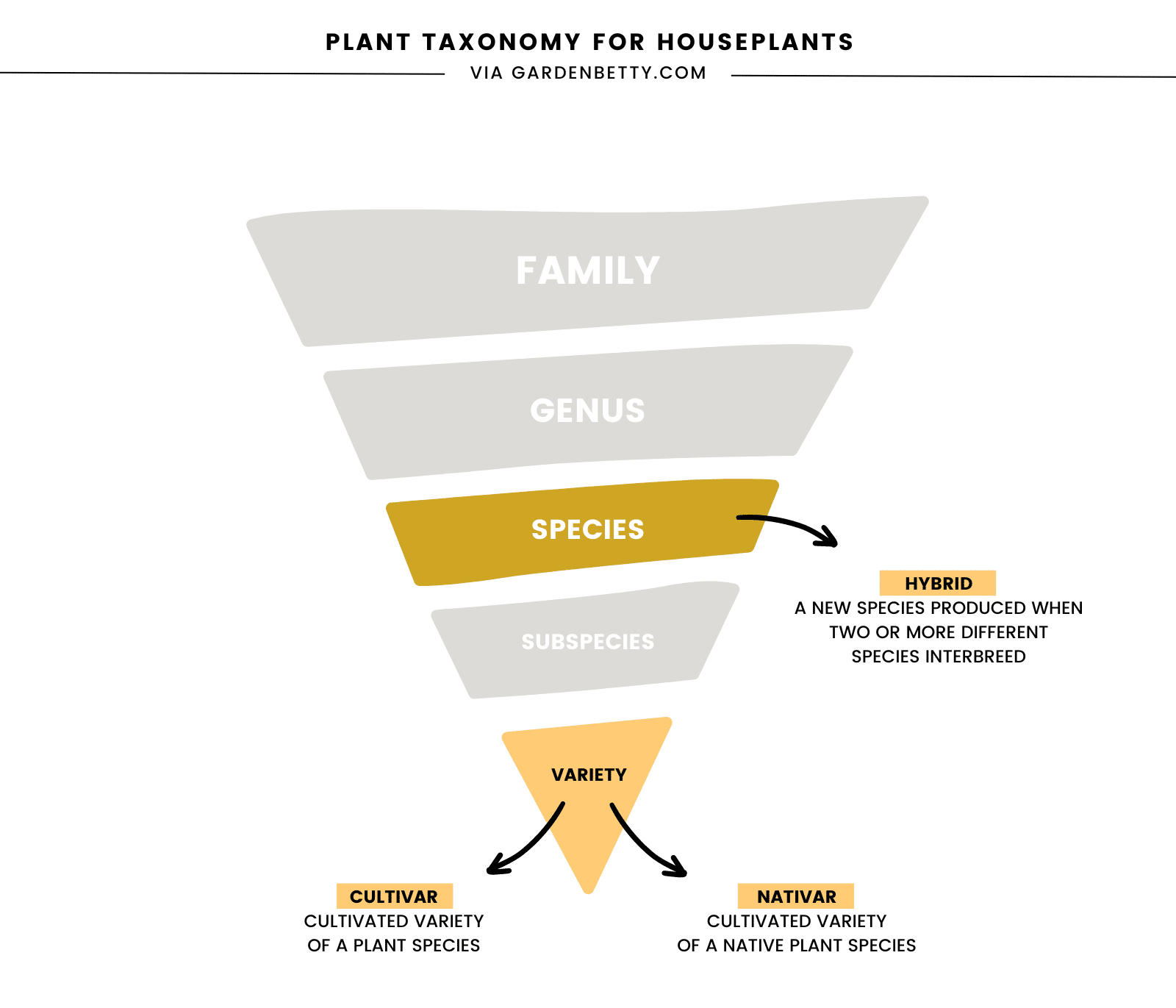

The taxonomical system of families, genera, and species that we just discussed applies to plants that occur in nature.

Of course, though, us humans can never just leave things be! We frequently take plants in their natural state and then gradually modify them to suit our needs.

The most poignant example of this are food plants. Take corn (scientific name Zea mays): before we began modifying it, the maize plant didn’t grow big cobs. It looked something more like a wheat plant.

Around 9,000 years ago in the area that is now Mexico, folks started planting kernels from the most desirable corn plants (with nice big cobs and plenty of edible kernels), for next year’s harvest.

By taking the best kernels each time, they gradually created corn plants with much bigger cobs and way more rows of kernels.

This brings us to cultivars, nativars, and hybrids. These all refer to certain adjustments made by humans to a naturally occurring species.

What is a cultivar?

The concept of selecting the most desirable specimens and continuing to breed them (selective cultivation) is also done with houseplants. It allows nurseries to create new varieties that are hardier and more decorative.

These are called cultivars.

If you remember that “cultivar” means “cultivated variety,” then you’ll have no trouble remembering the difference between a cultivar and a variety.

While a plain old “variety” is a naturally occurring phenomenon, a cultivated variety (“cultivar”) exists only through human propagation.

As an example, let’s say that a houseplant grower finds a Philodendron in his plant nursery that has pointier leaves than the other members of its species, maybe as a result of a genetic mutation.

Let’s also say that the pointy leaves look pretty cool, and the botanist in question thinks a plant with this look has commercial value. What they can do in this case is isolate the plant in question and produce more.

This can be done in one of two ways:

Method #1: Wait for it to bloom, then pollinate it using another plant of the same species. If the genetic mutation is stable, some of the seedlings may have pointy leaves as well.

The grower can then select those, breed them together, and eventually develop a line of pointy-leaved plants. However, these mutations aren’t always stable: the seedlings may come out looking normal and round-leaved.

Method #2: Propagate the pointy-leaved plant asexually by means of taking cuttings, or even through tissue-culture (which is basically propagation on a microscopic level).

The advantage of this is that the offspring is always identical to the mother plant.

Once a stable line of pointy-leaved plants has been established, a cultivar is born. The botanist can name them, which is done as such: Genus name + species name + ‘Cultivar Name’. It’s usually shortened to Genus name + ‘Cultivar Name’, though.

For example: Philodendron ‘Pink Princess’. Cultivars can even be patented!

What is a nativar?

You may have heard the term ‘nativar’, although it’s mostly used in gardening, not in the houseplant hobby. A nativar is simply a cultivar of a native plant.

The name is meant to convey that, yes, the plant in question is a native species. However, it has been subject to a certain degree of selective cultivation, meaning it’s not entirely in its “original” state anymore.

What is a hybrid?

Lastly, we’ve got hybrids. I’ve already mentioned that often, different species within a genus can reproduce.

What this means is that if our aforementioned botanist has one Philodendron species with nice pointy leaves, and one with decorative splits in its foliage, he might be able to pollinate one using pollen from the other.

The resulting seedlings will be a genetic mix of their parents. Some may look more like the mom, others more like the dad, and some may just look exactly like the grower wanted and have leaves that are both split and pointy.

They can now take these and keep breeding them together to create a stable line that always has pointy-split leaves.

A hybrid can be named in two ways. One is to go for Genus name + female parent species name × male parent species name.

Example: Philodendron pastazanum × mamei means the mom was a P. pastazanum and the dad was a P. mamei.

Alternatively, the hybrid can be given its own name. An example is Philodendron × Florida, which as we’ll see later, is a cross between P. squamiferum and P. pedatum.

This is where things get a little murky, though, as it always tends to do when it comes to man-made plants.

Often, the × will eventually disappear, with the plant being referred to more like a cultivar. After all, nowadays, you won’t see anyone writing Philodendron × Florida.

Instead, the plant is often called Philodendron ‘Florida’. Or even worse, Philodendron florida, which suggests it’s a species that occurs in the wild, when it’s not!

It doesn’t help that genetic mutations of hybrid plants can also be used to establish a new line and make whole new hybrid cultivars. There are multiple levels of human meddling there that can be quite difficult to distinguish, but hey—at least now you know why things can get so confusing sometimes.

Did you know? It’s said the first hybrid Philodendron was a cross between P. hastatum and P. erubescens, produced in 1936.

Source:

McColley, R. H., & Miller, H. N. (1965). Philodendron improvement through hybridization. In Proc. Fla. State Hort. Soc (Vol. 78, pp. 409-415).