What do these 15 vegetables and herbs all have in common?

- Watercress

- Chinese cabbage

- Chard

- Beet greens

- Spinach

- Chicory

- Leaf lettuce

- Parsley

- Romaine lettuce

- Collard greens

- Turnip greens

- Mustard greens

- Endive

- Chives

- Kale

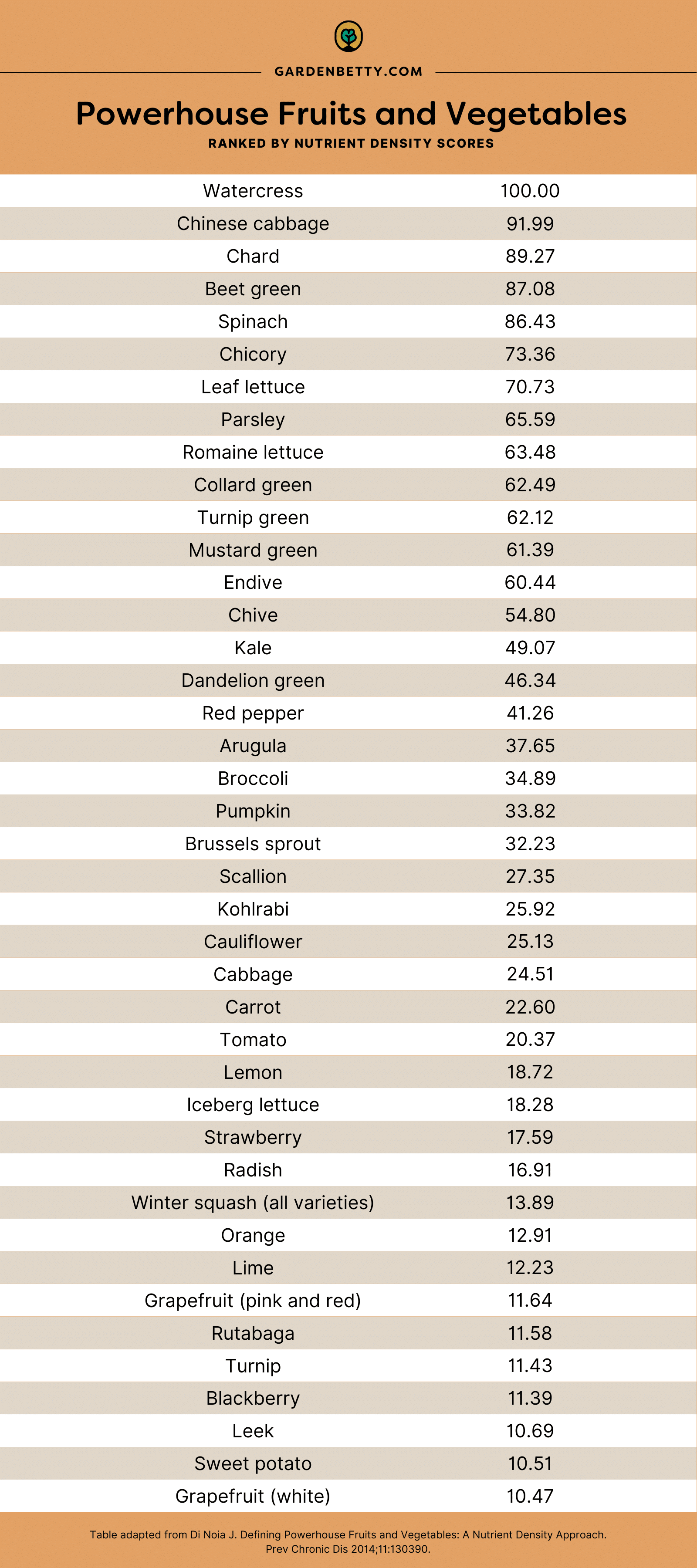

They’re the 15 highest-ranking plants on a list of 41 powerhouse fruits and vegetables (also known as PFVs), based on a study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

While the word “powerhouse” might make you think it’s nothing more than just another trendy health term (kind of like “superfood”), it actually does have scientific merit. Powerhouse foods are a legitimate classification for the super nutrient-dense fruits and vegetables that greatly reduce the risk of chronic diseases (such as cancer, diabetes, and heart disease). The PFVs that made this list have a high level of essential nutrients relative to the amount of calories they provide.

But there’s another common thread that gardeners, in particular, will find interesting… The top 15 on that list are all cold-tolerant vegetables. You might even be growing some of them right now, and in most hardiness zones, you can continue to grow them through the depth of winter without a greenhouse.

I’ve noticed that in my winter garden, these vegetables absolutely thrive compared to when I try to grow them in the heat of summer, which they often rebel against (think: early bolting (flowering) or tough and bitter leaves). And as we can see in the CDC study, the top half of the list (with the most nutrient-dense vegetables) is dominated by cold weather-loving cruciferous crops (watercress, Chinese cabbage, collards) and leafy greens (chard, beet greens, spinach).

What about the vegetables on that list that can only be grown in summer? Surprisingly, none of them had a nutrient density score above 42! Hmm… We may extoll the health benefits of our antioxidant-rich tomatoes, but apparently they can’t hold a candle to the nutrients in beet greens and leaf lettuce.

And that’s got me thinking… These cold-tolerant plants are able to survive winter by expressing special cold-tolerance proteins, accumulating sugars in their cells, and modifying their cell membranes to withstand freeze stress. Maybe—just maybe—some of these chemical adaptations also contribute to the benefits these plants have on human health? What if we learned that winter gardening is not only possible for most people, but healthier for us too?

Disclosure: If you shop from my article or make a purchase through one of my links, I may receive commissions on some of the products I recommend.

Growing powerhouse vegetables

The top 15 plants on the PFV list are extremely cold-hardy, and you can push their limits in winter (in USDA hardiness zones 5 and above) by growing them under a simple low tunnel covered with midweight frost cloth.

Related: How to choose between fabric and plastic row covers

Gardeners in colder zones can grow them in spring or fall (for better flavor and production). Most of these vegetables also grow well indoors in front of a sunny window.

Watercress, which tops the list with a nutrient density score of 100, is actually a perennial in zones 6 and above (possibly zone 5 with winter protection). It makes an excellent addition to your perennial vegetable garden (and no, watercress does not need to be grown in or near water—it just needs consistently moist soil).

Nutrient-dense chives, which also made the list, are a must in every perennial herb garden. They’re so prolific that the original six bunches I planted years ago have multiplied into dozens of bunches that I’ve transplanted around the garden and given away to friends. And because I love a multipurpose plant, chives are one of the best pollinator-friendly flowers.

If you want to try something different, you can also amp up the nutrient density of powerhouse vegetables by growing them indoors as microgreens, which—ounce for ounce—have more nutrients than mature plants. (Mustard and turnip microgreens are among my favorites for salads; I get my sprouting seeds here.)

LED grow lights let you grow cold weather vegetables indoors during the heat of the summer while producing minimal heat. Solar panels can drive the lights and cooling.

Yes, that’s one way you can do it! But a benefit of growing cool-season crops outside in spring/fall is that some of them will actually improve in flavor when exposed to very cold weather.

Back in the early 1970’s Scientific American published an article in which food scientists of the time rated the nutritional value of vegetables and also the contribution to American diets of the same vegetables. Tomatoes rated low in the comparison of raw nutrient value but contributed most nutrition to American diets because of its popularity in everything ketchup to BLT’s. Broccoli rated highest in the Sci Am rating for relative nutritional value and more or less changed places with tomato in the actual contribution to our diets, because as a people, we eat less of it than tomatoes. We know more about nutrition nowadays, but I think the difference between broccoli’s standing in the list you cited and the Sci Am rating a half century ago is probably the weighting of various nutrients. In my view, broccoli gets more nutritious after you harvest the head and grow the side shoots. There you have leafy greens thrown into the mix, all green (unlike head cabbages). Of course to get side shoots after ‘main’ harvest, you have to grow a variety that produces them. Deer and woodchucks permitting, here in Vermont I’m sure we get more nutrition from side shoots than from the ‘main’ harvest. And we do not need plant a succession plant to get it. In north-central

Florida, where the deer were more cooperative (lightly browsing here and there) and there were no woodchucks, the side shoot season was AT LEAST two or three times the season when the central flower buds were harvested. I developed a pruning system that stimulated side shoot production and the harvest often continued through winter until the first truely hot days of the following year.

The problem with rating systems, whehter in the 1970’s or now, is they do not compare the full range of nutrients, so tomatoes or watermelon contribute lycopene whereas the leafy greens do not. A varied diet will trump focusing on one or a few foods every time. We are omnivores.

I agree with you. The CDC study only looked at a select range of nutrients to determine their powerhouse fruits and vegetables, and it’s an imperfect list since nutrient levels can vary depending on the cultivar, weather, and other factors. I’m always of the belief that variety and moderation is best when it comes to consuming food. But, I still think this is an interesting look at where certain foods fall on the list—I never would’ve guessed watercress to rank so highly, as it’s not a vegetable most people grow or eat on a regular basis.

Great article. Thank you for writing.

You’re welcome Donna!