If you think about it, wild food is everywhere around us. Our backyards have dandelions growing so rampant, we constantly try to eradicate them.

Public fruit trees beg to be gleaned, miner’s lettuce is a weed with a gourmet reputation, easy hikes will bring you upon scores of stinging nettles and fennel.

Read more: Other common weeds that are actually edible

The East Coast has ramps springing up every year in shady woodlands. Northern California has chanterelles and blackberries in abundance.

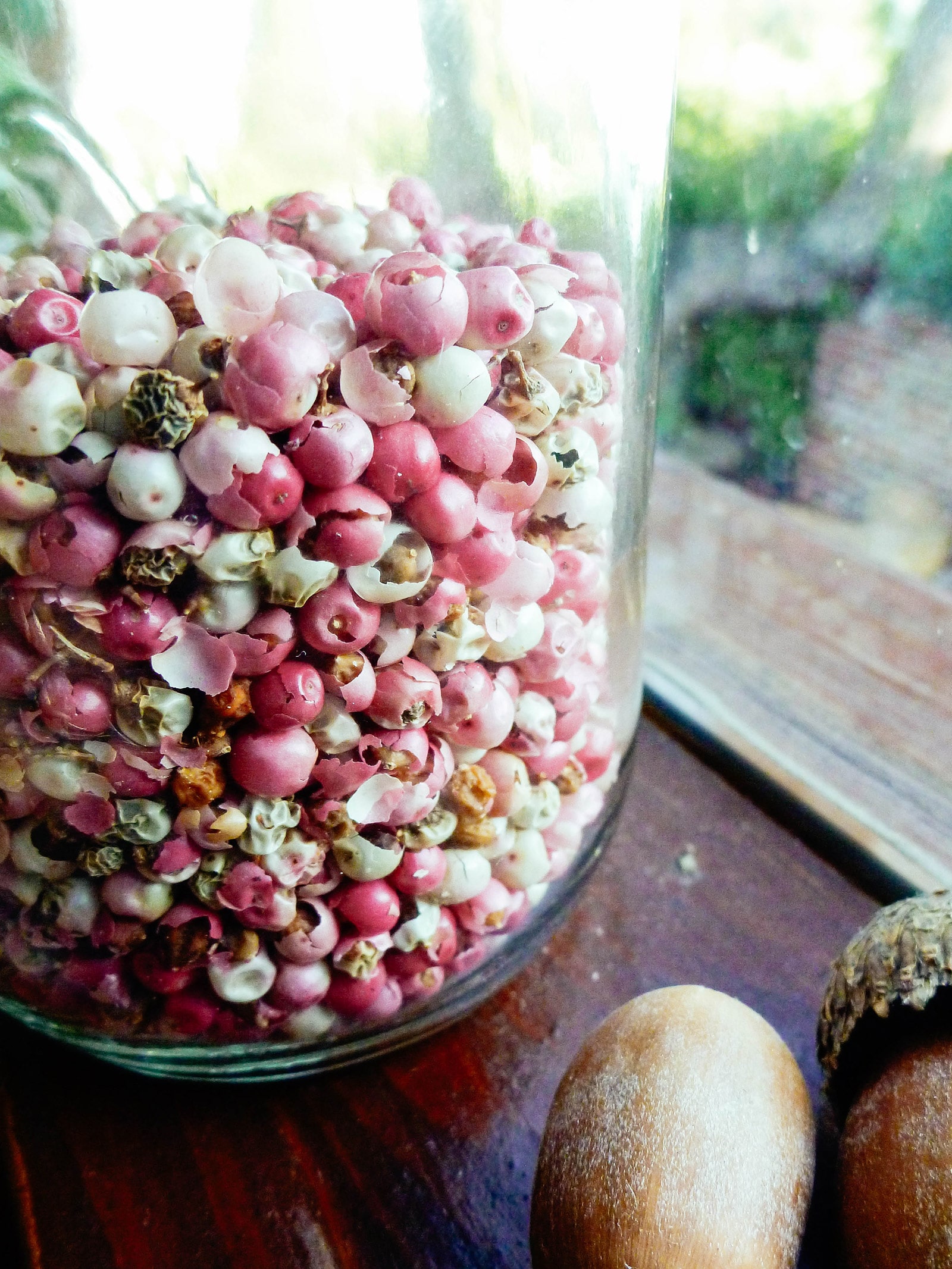

And in Southern California, there’s Peruvian pepper, also known as the pink peppercorn tree. These are the same pink peppercorns you see in stores as a gourmet spice, packaged in small, expensive jars and called for in fancy cookbooks.

But in Southern California and other parts of the country, bucketfuls of these vibrant berries litter the ground in suburban neighborhoods all through fall and winter, free for the taking. More often than not, they’re dismissed as a nuisance by the gardener who has to rake them all up.

It almost seems like a food crime to let heaps of peppercorns lay forgotten when just a few miles away, they command upwards of $10 an ounce at specialty spice shops.

Because while they look like (and are often grown as) landscape ornamentals in residential backyards and municipal sidewalks, the pink peppercorns from Peruvian pepper trees are 100 percent edible!

Related: Common vegetables you grow that you didn’t know you could eat

Peruvian pepper tree vs. Brazilian pepper tree

The classic pink peppercorn comes from the Peruvian pepper tree (Schinus molle), which is also called the California pepper tree (although it’s particularly invasive in Florida and Hawaii).

Peruvian pepper is not to be confused with its cousin, the Brazilian pepper tree (Schinus terebinthifolius), which has similar berries but rounder and wider leaves resembling holly. (And to make things more confusing, the pink peppercorns from Brazilian pepper trees are sometimes called Madagascar pepper—but they are one and the same.)

Though they are different species, the dried reddish-pink berries of both trees are used in commercial peppercorn blends, and are labeled interchangeably as “pink peppercorns” or “red peppercorns.”

The pink peppercorn tree featured here belongs to a friend and reaches over 30 feet in height—towering above his two-story home in Long Beach, California. Its drooping growth habit reminds me a lot of weeping willow, with evergreen branches that dangle with clusters of pink berries.

The berries are known as drupes, or fruits that bear a single seed. The hard, woody seed (wrapped inside a papery pink husk) is the “peppercorn,” though Peruvian pepper is not an actual pepper at all.

Pink peppercorn has no relation to the green, black, or white peppercorn berries (Piper nigrum, or true pepper) grown throughout Asia and used as a spice. It’s known as a “false pepper” and is actually a member of the cashew family.

(This connection to cashews is what gives pink peppercorns an unfair reputation as being poisonous—more on that below.)

Where are Peruvian pink pepper trees found?

Peruvian pepper is an evergreen tree with a weeping canopy of branches, native to Northern Peru in the high desert of the Andes.

It’s become naturalized around the world, where it’s cultivated for spice production, and in some parts it’s even considered a serious weed—taking over savanna and grasslands in South Africa, and forests and coastal areas in Australia.

Peruvian pepper likes hot climates and can be found in the Southwest (Arizona and Southern California), Northern and Central California, Texas, Louisiana, Florida, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico.

In Southern California where I first encountered them, Peruvian pepper trees grow wild all over the Palos Verdes Peninsula, as well as the Greater Los Angeles inland valleys and foothills.

I’ve foraged berries from my former backyard in the South Bay, my friend’s backyard in Long Beach, and from Piru Creek in Northern Los Angeles County. You can even find rows of pepper trees lining the streets around Disneyland in Anaheim!

The leaves and flowers of Peruvian pepper trees have a subtle peppery aroma. In spring and summer, tiny, delicate flower buds dot the branches. In fall and winter, the flowers give way to reddish-pink berries that are ready for harvest.

With Peruvian pepper trees ripening in fall and winter, the end (or beginning) of the year is the perfect time to start foraging!

How to harvest the peppercorns

Harvesting pink peppercorns is as simple as collecting a few clusters of berries from a Peruvian pepper tree.

Step 1: Look for branches with ripe pepper tree berries.

Cut off a segment of branch with a good amount of reddish-pink berries on it. They’re easy to find as they’re usually the clusters draping off the ends of the tree.

Step 2: Dry the peppercorn berries.

Gently pull the fresh berries off the branches with your fingers. Sometimes I’m able to do this quickly by running my fingers firmly down a branch to strip off the berries (the way you might take thyme or rosemary leaves off a stem).

Don’t worry if you get some stems in the mix—though it won’t give you a “clean” harvest, there’s no harm in having a few bits and pieces of stems in with your spice.

Spread the berries out on a plate or cookie sheet, and leave them out on the counter to dry at room temperature.

Within a few days, the berries will fully dry and harden into peppercorns.

A Peruvian pepper berry consists of a shell surrounding a single seed. During the drying process, the shell may crack and separate to reveal a brownish pink seed inside.

This separation is similar to how white peppercorns are made—the outer shells are removed from the berries of black pepper plants and the seeds themselves become white peppercorns.

If your berries are dried in a sunny spot, the shell may become bleached as it shrinks around the seed to create the hard, wrinkled outer layer so familiar as peppercorns.

Sometimes the shell stays intact and you’ll have smooth peppercorns, but you can eat any of these pink peppercorns (shelled or not).

What can you do with pink peppercorns?

Because of their delicate, paper-thin skins (which tend to get stuck in a traditional pepper grinder), I like to grind my pink peppercorns with a mortar and pestle, or crush them with the flat side of a heavy knife to release their oils.

I don’t blend them with black and green pepper (the way you typically see pink peppercorns sold in the store), as I feel true pepper overwhelms them.

Pink peppercorns taste differently than black peppercorns. They have a fruity and slightly spicy profile (like mild chile peppers) that complements seafood, salads, curries, cheese, chocolate, or popcorn.

Since Peruvian pink peppercorns are relatively mild, they can be used whole in recipes without being too overpowering. They’re still spicy and peppery, but have a very fragrant, sweet-tart and rosy tone.

The flavor would work well in light sauces, fruity vinaigrettes, or desserts. I think I’ll even try them in place of black peppercorns in my pickling spices, especially when I want a bit more sweetness.

Make this: 4 easy ways to pickle green tomatoes

As with any spice, pink peppercorns should be stored away from direct sunlight and heat to preserve flavor. It will keep for at least six months, after which it may start to decline in quality (which simply means you’ll have to use more of it to get the same potency as freshly dried pink peppercorns).

Read next: Organize your spice drawer with my simple DIY hack

Are pink peppercorns toxic?

Here’s an interesting chapter in the pink peppercorn tree’s family history that most people don’t know…

The Peruvian pepper tree belongs to Anacardiaceae, otherwise known as the cashew family, a group that also includes poison sumac, poison oak, and poison ivy. Pink pepper’s connection to this notorious family means it earned a bad rap in the 1980s for being a potentially toxic plant.

That’s because the Brazilian pink pepper was once banned from importation after the Food and Drug Administration received reports of consumers having adverse reactions to the berries.

It enjoyed a brief moment in the culinary spotlight when it was introduced in 1980, hailed as an emblem of French nouvelle cuisine.

But researchers soon began documenting cases of human toxicity including “violent headaches, swollen eyelids, shortness of breath, chest pains, sore throat, hoarseness, upset stomach, diarrhea, and hemorrhoids,” symptoms that are consistent of those with poison ivy reactions, according to this 1982 article by The New York Times.

The French government protested the FDA ban, insisting that pink peppercorns grown and imported from the island of Réunion, near Madagascar, were non-toxic due to the trees growing on different soil under different conditions.

With uncertainty on whether or not they’d poison their customers, chefs stopped cooking with pink peppercorns, markets stopped selling them, and the once-trendy spice fell out of public favor by 1983.

The French eventually submitted research that proved their Brazilian pink peppercorns were non-toxic, and the FDA dropped its ban. Rainbow peppercorn blends gradually made their way into shops and kitchens again, with few answers to explain the spate of severe reactions that were previously documented.

Today, it’s believed that allergic reactions are limited to people who are allergic to tree nuts (since pink pepper trees come from the cashew family) or those who are sensitive to the sap of poison ivy.

What’s not known is how much of the spice one has to ingest in order to experience any ill effects. Most people don’t chew on handfuls of pink peppercorns at a time, so with the tiny amounts used in cooking, it’s unlikely to cause reactions in those without serious allergies to related plants.

In addition, there have been no documented cases of people experiencing reactions to Peruvian pink pepper. It’s widely enjoyed these days in all types of cuisine, whether the peppercorns are purchased from a store or foraged from a tree.

Do you have a pink pepper tree growing in your yard? Or do you live in an area where pink pepper trees grow in abundance? Please share where you’ve seen them!

This post updated from an article that originally appeared on November 10, 2011.

Interesting thank you.

I am living in the South Island of New Zealand (Canterbury) and have discovered several pink pepper trees in this valley.One huge tree, outside a hotel built in the 1870’s, has an enormous tree in its outside courtyard.I’ve not met any local resident yet who knew what these trees are.

Great information for folks in California. Do you have anything for those of us in wintery cold Connecticut?

Thanks!

Pink pepper trees are hardy to zones 8 and above. I’m not sure if Connecticut falls within that range?

Wow – thank you for this article. I lived in Florida my whole life and the Brazilian pepper trees were always dismissed as an invasive nuisance…..I only recently started to try and understand everything outlined in this article and was very confused about the toxicity of the Brazilian pink pepper because the info seems confounding.

I would love to forage these!

Brazilian pink pepper is not toxic. But people who are allergic to tree nuts may be sensitive to it, since Brazilian pink pepper is in the cashew family. If you can do cashews, you should definitely harvest a few pink pepper stems while the berries are ripe!

I have couple of pink peppercorn trees in my garden with alot of pink peppercorns! I found your article very useful. I live in Canary Islands, Spain.

Enjoy them Cheryl!

I live in Saratoga, CA (40 minutes south of San Francisco, and these trees grow all over. This is my second year harvesting the pink berries from Nov. through Jan. and I put them in my commercial food drier for over a week on low temp. hoping they will turn black. I peel the pink skin off and then oput them in my pepper grinder. Great aroma–not as strong as regular black pepper.